When I first read St. Augustine’s Confessions in college, what made me almost weep for joy wasn’t the biographical account of his conversion, as moving as that is — and as deeply as I appreciate it now, particularly after translating his work. It was his wondrous exploration into the nature of memory, form and matter, the beginning of creation, and time. The last few “chapters” of the Confessions are only a few sentences each, but I do not think that more has ever been said in prose, in such a powerfully small space. It’s as if Augustine’s mind itself were like the seed of creation, ready to burst into being at the bidding of God. Those last sentences have to do with our Word of the Week, eighth, as I’ve said, because Augustine is yearning for the Sabbath beyond the Sabbath, and is knocking at the door, to receive what can be given to man not by another man, nor even by an angel, but only from God.

I was learning at that time, too, from a few of my professors at Princeton (of all places), that medieval and Renaissance artists and poets thought of number as trembling with the music of creation and of God’s providence. Dante could not just have any old number of cantos in his Divine Comedy: there had to be 100. And he could not parcel them out randomly, either. I’ve heard it said that each of the 3 realms of the hereafter have 33 cantos, with the first book, Inferno, including an extra one by introduction. But that’s not accurate. The number symbolizing Christ is 33, his age when he died and rose from the dead, and Hell, with either 34 or 32 depending on how you look at it, errs by excess and defect both: it isn’t worthy of a clean 33 cantos. Of course, Dante invented his poetic form, the terza rima, three-line tercets interlocking with rhymes from one to the next, in homage to the Trinity. Dante wasn’t alone, as I learned. Petrarch did that sort of thing. The Pearl-poet did it. Chaucer did it. So among English Renaissance poets did Sidney, Spenser, Herbert, Milton, and many others, perhaps even Shakespeare. And I determined, when I wrote The Hundredfold, that I was going to learn from those masters too. That is why I’m giving you this poem from that work, in commemoration of Easter and the Sabbath beyond the Sabbath.

Each of the lyric poems in The Hundredfold is introduced with a verse from Scripture. This one is headed thus: “If you are in Christ, you are a new creation.” It is the 34th of 66 lyric poems, capping a central section of the work — a section with lyric 33, then five hymns, then lyric 34, this one I am sharing with you today. Lyric 34 from The Hundredfold, is about the Resurrection, but I present it in the structure of meditations on each of the 7 days of Creation, in Genesis. Each of those 7 stanzas has 7 lines of iambic pentameter. The eighth stanza is a rhyming triplet, in italics: as if it were beyond the previous seven, but summing them all up. That makes 49 + 3 lines, as if the triplet lines were a “jubilee” making 50. There’s more, if you’ll indulge me a little farther. The square of 7 is 49, of course. Since the meter is iambic pentameter, that gives us 490 beats or what count as syllables, weak or strong, in those 7 stanzas. But the eighth and final stanza of the poem, a triplet is different in measure: it has 7 + 7 + 8 = 22 beats. The total for the poem is then 490 + 22 = 512, and THAT is 8 cubed. There’s more — but that’s enough for now. (My wife is rolling her eyes at me as I type this explanation of that single poem’s structure!)

As you listen to or read lyric 34 from The Hundredfold, you’ll notice that creation is involved with, or assumed up into, re-creation in each of the stanzas. We’re too apt to think, in our time, only of the material that makes up a thing, or perhaps what caused it to exist, but not enough about what it really is, which would lead us to consider where its perfection lies, where it is going, and what its part is in the great symphony of being and significance that the divine Composer has sung. Each of the gospel writers, whether grandly and magnificently as John, or tersely and modestly as Mark, sees everything that exists in the light of the Resurrection: thus the beginning of all things is involved in the consummation. That’s what I try to do also in this poem. And by the way — the rhyme scheme is Dante’s, terza rima.

But even if you didn’t know anything about the structure of Lyric 34, its meaning is clear, because I do write to be understood. Truth comes first, and beauty — if the artist can accomplish it — is in the service of truth. And now I’ll repeat the prayer I ended with on Monday: May the Lord who made this world in measure, weight, and number shower his blessings on you and your family, and may this Eastertide be for you an earnest of that morning star that never sets.

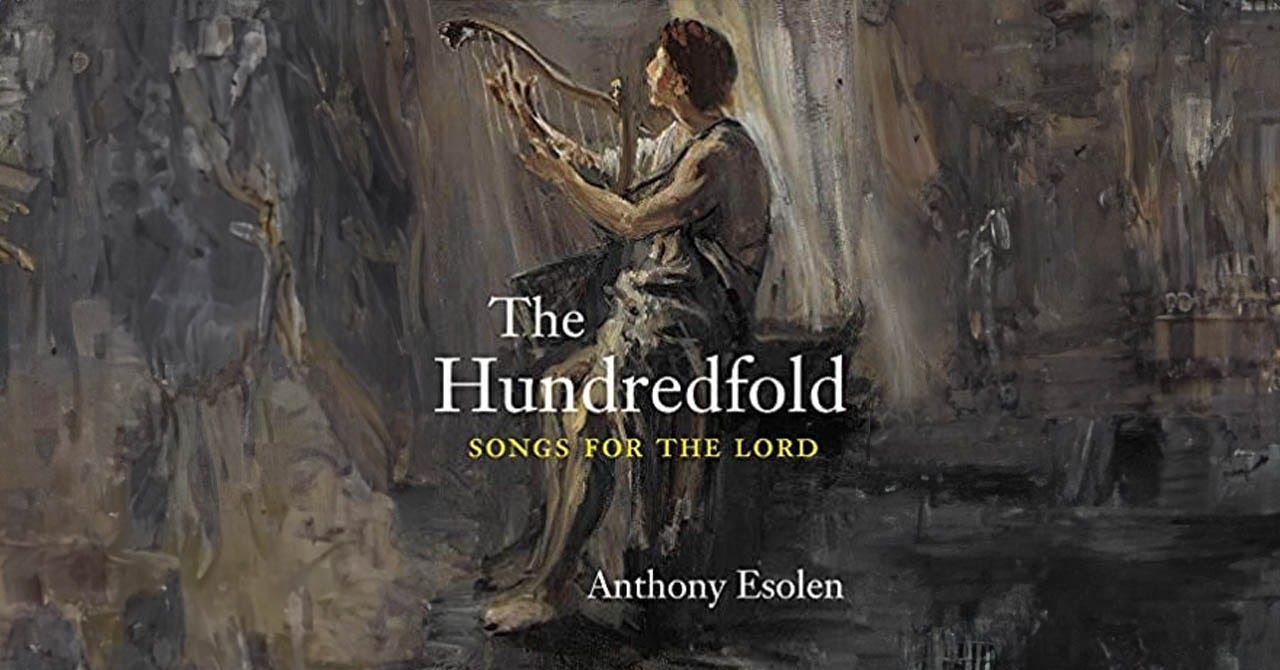

The Hundredfold: Songs for the Lord

“How does one describe a work as rare, as priceless, as this? Nourishment for the malnourished soul. Food for those hungry for beauty. Manna in the desert of our postmodern waste land. Lembas for sojourners in Mordor. All we need to do is taste and see that it is good!”

1 Amid the chaos and the night of man,

Who shuts his eyes in terror, lest they see,

Who puts the Spirit of God under the ban

Because he does and does not wish to be,

And lest he learn obedience and delight,

Leaps headlong into vast vacuity,

Breaks from the tomb the uncreated Light.

2 Tear then the Temple firmament in two,

Impetuous Bridegroom, pierce beyond the veil

And lay the luminous heavens bare to view;

Strip off the false flesh of our souls, and hale

Beings newborn to stand before Thy throne

Naked in individual detail:

Themselves at last, because they are Thine own.

3 Feel now the tremors of the barren earth;

She who was old and dry, a branchless stock,

Shudders in the forgotten joys of birth;

The seas swell, and the nations feel the shock,

While all is shaped and shifted in that flood

Which Christ has broken from the bordering rock:

Even his heaven-and-earth commingling blood.

4 No more we need the pale light of the moon

To tell us when to till the earth for seed;

Her final pilgrimage is coming soon;

The sun shall rest, and let his fiery steed

Drink from the freshets of eternity.

We follow where the Morning Star shall lead;

He is our day, and all our seasons He.

5 When Noah freed the dove to search for life,

She brought a branch of olive, fresh and green;

So from the ark he tottered with his wife --

Eight souls in all beheld the quiet scene.

Well that it then should be a heavenly bird

Feathered as a young man of peaceful mien,

To bear the tidings of the risen Lord.

6 Over the man the brute beast long held sway,

And he in his slouched mind imagined God

Like to the stolid ox that munches hay,

Leviathan of the deep, or, stuffed with fraud,

Some mannish serpent. But the great I AM

Re-formed man from the dust that Jesus trod,

And raised him up to godhood by a Lamb.

7 From the tomb breaks the uncreated Light!

O let there be no little work today,

But we shall flex our hearts with all our might

To lean into the angels' songs, and pray,

Flushed with the sweat of a new-risen boy

Who greets the morning in its glad array.

O the energy of peace, the play of joy!

8 Thus begins with songs to Thee,

God whose essence is to be,

The day that is eternity.Listen to this episode with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Word & Song by Anthony Esolen to listen to this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.