As you may have surmised from my essay for our Word of the Week, music, I think there’s a real mystery in why we sing, and how and when and what we sing. Let’s step back and think about it. Suppose you ask a friend who does a lot of driving, “What’s the best way to get to New York from here?” You expect straight information. “Take Route 7 west, then go straight down the Thruway. It’s a little longer in miles, and part of it isn’t highway, but I guarantee you that if you go down to catch this highway here,” he says, pointing to a “map” on the palm of his hand, “the traffic will sludge you up. That’s if you don’t travel late at night.” You may get a little of his personality, but not much. Or suppose you are chatting, trading stories about high school. You tell one story in which you play the buffoon or the hero or both, and then he tells the same about himself. You get a lot more of his personality, and you may get something of what he believes about the whole world, flickering like a star. But you still won’t soar. Or you won’t enter the depths of the soul. Or you won’t shine in complete self-forgetfulness.

But suppose your friend is out in the field, raking the hay, and he doesn’t know that you’re approaching, and you hear him singing, at the top of his voice — because nobody is nearby — an old jaunty folk song, like “Juanita,” or a patriotic anthem, like “The Maple Leaf Forever,” or a hymn, like our Hymn of the Week, “Children of the Heavenly King.” Why do you feel just a little bit embarrassed, as if you were blundering into something deeply private? And yet it’s the open air, and he’s singing, so you’d think he wouldn’t expect privacy. And maybe a part of it is just that we’re no longer used to singing, because we don’t know many songs, and we’ve been encouraged somehow to think that singing is just a little bit silly. But still — I imagine that with all the good will in the world, you and your friend might blush a bit, the color that Milton calls “celestial rosy red, love’s proper hue.” Singing, says Saint Augustine, is what the lover does. We sing, and we launch out into the realm of love — somehow or other, if we’re really singing and not groaning or grunting, that’s what we do, and innocence itself will blush.

“But the birds sing,” you may say, “and that’s just their nature. They don’t always sing for love, either, but to mark out territory, to give warnings, to tell other birds that there’s food nearby, and other practical things like that.” I don’t know if that’s strictly true. Who can tell how the great universal song of love is projected upon the harp that Mr. Cardinal sweeps, when spring is in the air? I don’t think it’s accurate to reduce what human beings do to what we suppose the animals do; more accurate to see in what animals do a manifestation of what the higher creatures do — what human beings and the angels do. When the old poets looked at the stars in the sky, at those grand creatures that are not even alive, they saw dance there, and the traces of a music only the mind can hear. I think that their sense was right and just.

So then, our hymn today is about singing hymns! It was written by a man named John Cennick, a friend and collaborator with John Wesley. He’d been raised a Quaker, drifted away into utter dissolution and sin, returned to God by the Methodist revival, then leaned hard toward Calvinism, and ended up a Moravian, dying at the young age of 36, leaving a wife and two children. He was by all accounts a tireless and courageous speaker, and a founder of dozens of churches. But what I find admirable about “Children of the Heavenly King” is that it can be sung by any Christian, aside from all controversies. Children are not too self-conscious to sing — a little encouragement will suffice. If we sing, if we give ourselves over to sacred music, we have to forget ourselves too, or at least try to forget and so half succeed at it. That is one reason why singing is what the lover does. For the lover isn’t preoccupied with himself; only with the excellence of the beloved. Now then, what if the beloved is Christ, and he is leading you in your journey through life? We may then not only sing about Him, or sing to Him, but also sing with Him.

The melody I prefer for our hymn is Melling, an air with happy runs of eighth notes, as in a lot of English folk songs. It fits perfectly, as I think you’ll agree. The composer was John Fawcett of Bolton (not the same as a John Fawcett who wrote the lyrics to “Blest Be the Tie That Binds”). Fawcett was mostly self-taught; the boy was an apprentice to a shoemaker, but he learned how to sing in the village choir, and that got him started in a musical career of considerable distinction, as a musician, a teacher of music, a conductor, a choirmaster, and a composer, with more than a dozen books of music to his credit. We may hope, then, that if God could raise up a shoemaker’s apprentice to such heights, He may well stretch a little farther and raise up even a college graduate!

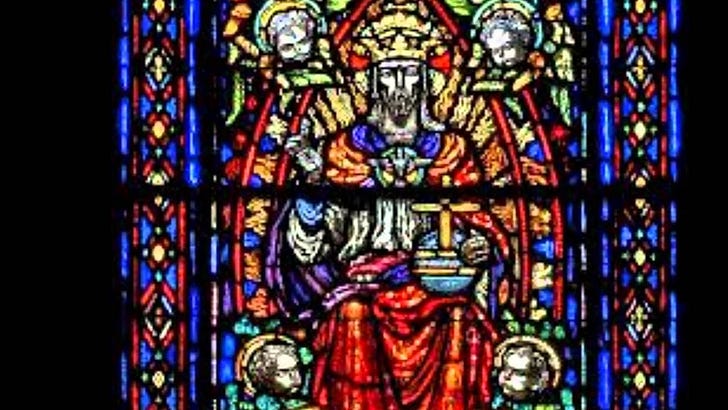

Here’s a splendid version of our hymn, by the Wakefield Choir — and a nice look at some stained glass windows, too.

Children of the heavenly King, As ye journey sweetly sing; Sing your Savior's worthy praise, Glorious in his works and ways. We are traveling home to God, In the way our fathers trod; They are happy now, and we Soon their happiness shall see. Fear not, brethren: joyful stand On the borders of your land; Jesus Christ, your Father's Son, Bids you undismayed go on. Lift your eyes, ye sons of light! Sion's city is in sight: There our endless home shall be, There our Lord we soon shall see.

Thank you for joining us at Word & Song.

Special: Upgrade to paid or give a gift subscription through Easter Week.