I mentioned yesterday in my discussion of our Word of the Week, mood, that we don’t now have a word that corresponds to the Anglo-Saxon mod, or its adjective modig, that combines ideas of energy, action, courage, mindfulness, and intense will. I still think so, but here’s an idea and a word that may come close: zeal. And sure enough, I will do that word someday, with its strange doublet of zealous and jealous. It’s not an exact fit, because what’s missing is the mental concentration, but the heart of it sure is there. So our Hymn of the Week, “Christ for the World We Sing,” is a song of passion and intensity, not of a glowering kind, but free-hearted and irrepressible.

I suppose there are several kinds of failings when it comes to such passion. One, the most common, is not to have much of it at all, to fail by defect. Imagine that someone goes up to a priest to ask him about the faith, and the priest, irritated to have his free afternoon interrupted, behaves as if the matter were of no importance. That will cut the heart right out. Another, common in certain settings, is to make a lot of noise, like a poor writer using the exclamation point all the time, as a kind of impostor of feeling. A third is to be passionate for the wrong things. I think that right now the Christians of Syria — and they are by no means the only ones in the world — can testify to what it is like when someone else’s misdirected and frenzied mood puts a target on your back.

But this “moodiness,” to update the Old English word from yesterday, is in itself a good thing and can be powerfully attractive. Here I think of what happened when Thomas Merton, then a young atheist, walked into a church in New York City one day when Mass was being said. Several things struck him. One was the resounding peace within, not peace as an absence of noise, but peace like a silent power. For people of all walks of life were there, and they seemed to him to be there with a will; I don’t even believe it was a Sunday. The priest gave a homily filled with theology that Merton didn’t understand, and in doing so he simply assumed that the people — doctors, students, housewives, tradesmen, pensioners, children — would understand him. In other words, there was a mental intensity to it, reflecting the spiritual intensity.

The power of that experience did not spring from arm-waving and shouting, but from that combination of courage and intellectual concentration that we hardly can describe. Here’s another example of it. Augustine met the same thing when he went to listen to the bishop Ambrose preaching in Milan. Now, Augustine was then, by profession, a teacher of rhetoric, so when he heard Ambrose, he was in part evaluating that good and brilliant man. Ambrose had a gravelly voice that tended to go hoarse, so the power of his preaching didn’t depend on that. He also spoke calmly, not calling down thunder and lightning. But he spoke with a passionate determination to reveal to his flock what was true, and to separate the truth from the most plausible errors. It’s a little like what Augustine and his friends saw when they occasionally went to visit Ambrose. They saw him reading silently. Believe it or not, it is the first account we have of someone doing that. In those days, you see, books were written without spaces between the words, making it almost impossible to read unless you were sounding out the words with your voice as you went along. But there was Ambrose, sometimes so intent on the meaning, that he didn’t even hear when someone had entered the room.

Now imagine that it’s not you alone who are driven by this passionate vision of the truth, but you and your fellows singing a hymn together. That’s what we’ve got in the rousing and bold “Christ for the World We Sing.” The author, Samuel Wolcott, knew whereof he wrote. He had been a missionary in the Middle East when the British liberated Syria from the Ottoman Turks; poor health compelled him to return to the United States, where again his work was tireless as a lecturer, a preacher, and an organizer of missionary efforts. Zeal ran in the blood, it seems: his grandfather Oliver Wolcott was one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence, and his youngest son, Edward, enlisted in the Union Army at age 16, later becoming a United States senator from Colorado. A bit of trivia: Wolcott, Colorado is a tiny hamlet with a population of 20, through which passes the same 3100-mile-long road that goes through my home town: US Route 6, otherwise known as the Grand Army of the Republic Highway.

Such a grand hymn — Christ, for the whole world!

Debra searched to find grand version of our hymn, sung by the Sanctuary Choir, accompanied by Paul Butt, organist, at First United Methodist Church of Houston, Texas. Stay tuned at the end of the video for another great hymn, “Christ lag in todesbanden” (Bach).

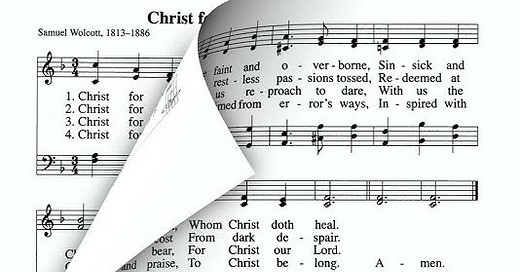

Christ for the world we sing! The world to Christ we bring With loving zeal; The poor, and them that mourn, The faint and overborne, Sin-sick and sorrow-worn, Whom Christ doth heal. Christ for the world we sing! The world to Christ we bring With fervent prayer; The wayward and the lost, By restless passions tossed, Redeemed at countless cost From dark despair. Christ for the world we sing! The world to Christ we bring With one accord; With us the work to share, With us reproach to dare, With us the cross to bear, For Christ our Lord. Christ for the world we sing! The world to Christ we bring With joyful song; The newborn souls, whose days, Reclaimed from error's ways, Inspired with hope and praise, To Christ belong.

Paid Subscribers have access to our full archive, on demand. Thank you all for supporting our work at Word & Song!

I did not see the Bach video, alas; I think what YT shows next differs for each viewer.