“Who was the greatest of all the Greek heroes?” a boy in the old British schools might ask, and it’s not an easy question to answer. We might say, “Hercules was!” — except that Hercules is a borderline case, a demigod, and there are aspects to his story that don’t fit the heroic mold, as when he fell in love with Iole and for her sake took up spinning and needlework, while she put on his lionskin, ten sizes too big, and tried to lug his club around. Anyway, if we’re really after the peculiarly human, even if he’s got a divine parent, the two great figures of Homer’s poetry stand forth, Odysseus and Achilles. I love Odysseus, the man of many shifts, a broken-field runner if there ever was one, feinting left and darting right, a man of brains and courage, whose main aim in the Odyssey is to get back home to Ithaca, sort of like wanting to get back from the Ardennes to the Ozark Mountains. Yet after Homer, judgment begins to tilt away from Odysseus, who is often portrayed as a liar and a cheat: “The inventor of impieties,” Virgil calls him. And then there’s Achilles, and the first lines in the Iliad bring us both him and our Word of the Week, hero.

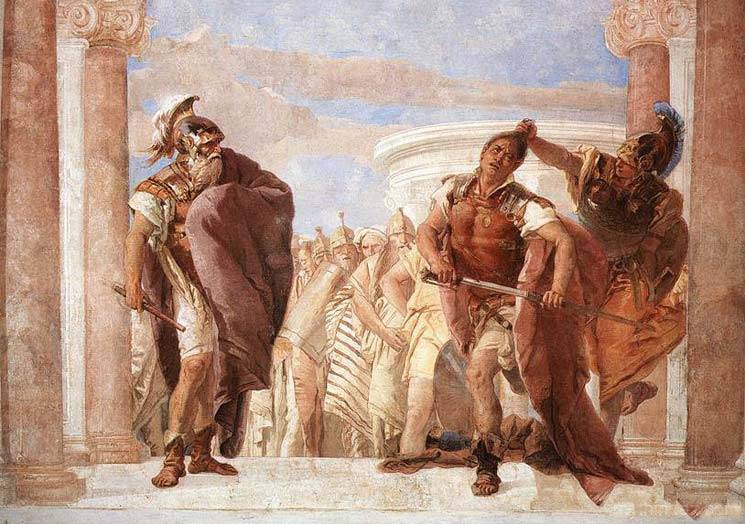

“So then,” says the curious boy, “that’s where Homer first calls Achilles a hero?” No, he doesn’t. This is what Homer says, if you’ll let me translate it in prose so as not to break up the visuals here on the page: “The rage of Achilles son of Peleus, sing to me, Muse, that dire rage that brought pain to many an Achaian, that pitched many stout-hearted heroes to Hades, and made of their bodies a feast for the birds and the dogs.” Good gracious, nobody writes poetry like that anymore! But wasn’t that what Achilles was supposed to do? No, not at all. The Achaians were his own people — and his implacable anger against King Agamemnon caused him to duck out of the war, leaving his own side vulnerable; but in his terrible fury he wanted to see them die, so they would learn the hard way what chance they had against the Trojans without him. Hardly four lines, and we’re stunned. The heroes named are those who died while Achilles was sulking, Achilles the hero.

What does it mean to be a hero? Our last Film of the Week, Sergeant York, featured an American hero of the first order, a man of peace who gave up his comfort to fight so that others might live, and who methodically, and pretty much single-handed, took out a whole nest of German machine gunners, and led away as prisoners of war 132 surprised and abashed German soldiers. Of course, we can use the term metaphorically, to refer to anyone we admire. “He’s mah i-deel!” said Li’l Abner, who loved to read about Fearless Fosdick in the funny papers, Al Capp’s merciless sendup of Dick Tracy. But in the most fundamental way, heroism is courage under ultimate threats, such as death or destruction, or the risking of all that you have and enjoy. The guys who brought Flight 93 down in western Pennsylvania were such heroes: they might have held out some slender chance of surviving, not knowing with absolute certainty what the hijackers intended, but they bravely tossed that chance away.

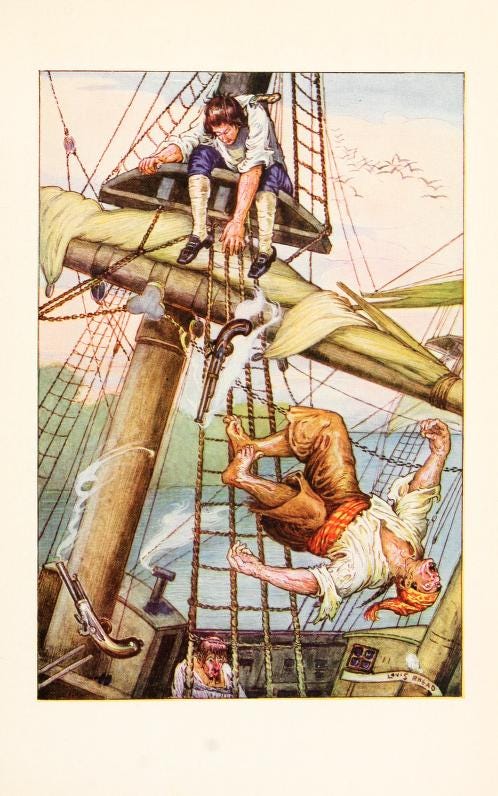

I’ve said that all cultures have heroes, but since ultimate matters are in question here, it may not be so simple after all to determine who the hero is. That’s especially true in Christian cultures, since the hero Christ conquers death by dying, so that, to use Milton’s words, “heavenly love shall outdo hellish hate.” Suggestions of this surprising inversion can be found in pagan cultures — “good dreams,” as Tolkien called them, but they’re common in Christian literature, these heroes where you least expect them. The boy Jim Hawkins in Treasure Island is a hero not just because he is brave and resourceful, but because he remains stoutly loyal to his friends even when they believe he has betrayed them, and he knows that they believe it. In David Copperfield, the schoolboy David looks up to Steerforth as a hero, because Steerforth protects him and is afraid of nobody, but we see true heroism in Mr. Peggotty, traveling all over Europe in his quest to find his niece Emily and bring her safely home, after Steerforth has run away with her. That old tar is as tough as oak, and filled with the energy of love. Again Milton’s words apply. Milton didn’t want to write a long poem about war, “hitherto the only argument / Heroic deemed,” which left “the better fortitude / Of patience and heroic martyrdom / Unsung.” Always he has the Son of God in mind.

We get our word hero pretty much intact from ancient Greek heros, borrowed straight into Latin, descending into French and from there into English. But of course we had the idea before we had this particular word. Our native word for it was haeleth — with an underlying idea of giving wholeness or increase. That’s the word the poet of The Dream of the Rood uses to name Christ, the young hero striding from afar to embrace the Cross and liberate all mankind. In English, hero displaced haeleth, but that word’s close cousin survived in German: the hero is der Held. Any distant cousins? That’s hard to tell. The guess is that Greek heros is a cousin of Latin servus, servant, of all things, but the servant considered as one who guards, protects. But isn’t that a stretch, to have a word beginning with s- related to one beginning with h-? Not if we’re talking about Greek, and the s- was followed by a vowel. So we have Latin sol, sun, but Greek helios (whence English helium), and Latin sal, salt, but Greek halos (whence English halogen, a salt-making element). How odd, and yet appropriate, if the words heroic and serve were akin!

Note: Our full archive of over 1,000 posts, videos, audios is available on demand to paid subscribers only. We know that not everyone has time every day for a read and a listen. So we have built the archive with you all in mind. Please do browse, and please do share posts that you like with others.

Thank you, as always, for supporting our effort to restore every day a little bit of the good, the beautiful, and the true.

Share this post