I may have mentioned this before, but I’ve taken up a challenge I left off thirty years ago: I’m setting out to memorize Paradise Lost. I’m about 300 lines into Book Six, so that’s about 4800 lines, a little under 46%. Anyhow, when you take a great work of Baroque art this carefully, the intricacy and precision and exquisitely careful interlocking of motifs come across with great power. Imagine going through a Bach fugue, measure by measure, committing it to memory and thinking all the time, “Why did he put those notes there in that order?” And the closer you look, the more it staggers you. It might be like the experience a biologist would have had as he looked into the workings of a cell — which in the nineteenth century was considered rather like a blob of jelly with a shot of electricity to jolt it to life, but now we know is like an enormous complex of interlocking factories; as if, the more you zoom in, the more it all opens out into a regular metropolis. It wouldn’t half surprise me to find street signs and sub-cellular Irish cops walking the beat.

That’s to look deep into the smallness of the cell and find magnificence; but haven’t I mentioned that in many languages, the words for deep and high, our Word of the Week, are the same? Fittingly so for our author today for our Poem of the Week, John Milton. You see, if you’re going to write an epic poem about the Fall of Man, you can’t omit the Fall of Satan and his rebel angels, and indeed for hundreds of years those two events were bound together in the popular imagination. You’d see them almost one after the other if you were at any decent-sized town in Europe on the old three-day feast of Corpus Christi, because that’s when people put on a series of plays, staged on floats that would proceed from one station to another through the town, plays that took you from Creation (of the angels, even before the earth) to the Last Judgment. So you’d see the fall of Satan, quite literally, before your eyes — there are a lot of things you can do with trap doors and such, real crowd pleasers. “I saw Satan fall like lightning,” said Jesus.

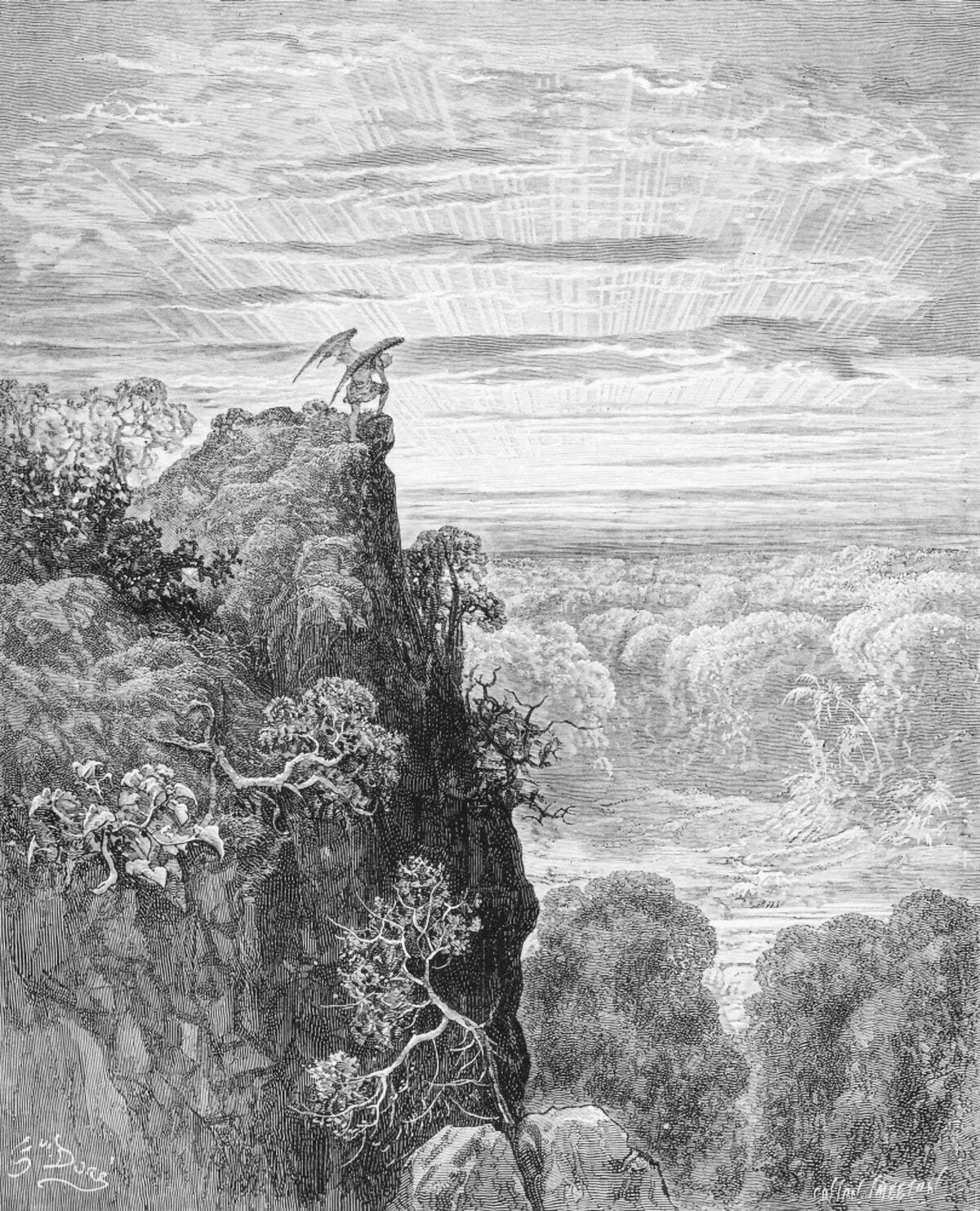

Now, height and depth are continual motifs throughout Paradise Lost, and though you may guess why it’s obvious that they should be so, what with the poem’s being about a fall from grace, still, Milton varies their use in innumerable ways. That’s partly because God wants man to rise: but the secret of rising is not ambition, but wisdom, filial obedience, trust in God’s bounty beyond thought, and faith. All created things are made so as to return to Him, upward, “unless depraved from good,” says the angel Raphael to Adam. Love desires that the beloved should be more exalted, and that’s why, before the Fall, Adam and Eve address one another in delightful honorific terms: “Daughter of God and Man, accomplished Eve.” They are, after all, the king and queen of the earth. Satan falls not because he wants to rise, but because he perversely wants a contradiction in terms, which is to rise apart from the Most High. That is, he wants to be a god, without God; it is like wanting to know without Intellect, to exist without Being.

So here, at the beginning of Book Two, Satan and his crew have been cast out from Heaven, and, attempting to put a flashy face on things, they have built up a great palace in Hell, Pandemonium, and that’s where Satan and his chiefs are now retired “in close recess and secret conclave,” apart from the rout of the thousands of others, to debate about What To Do Now. It’s presented as a democratic sort of thing, but that’s all on the surface, because what they decide is a foregone conclusion, determined by Satan and his right-hand flunky, Beelzebub.

Satan now presents himself to those other chiefs, Satan who has posed as a “patron of liberty,” whose every other word, when persuading the other angels to rebel against the Son of God, has been “equal.” How does he appear? Like the highest and most opulent of oriental despots. Nor is he satisfied with this height. Such ambition is like a never-stable crater, always caving in underneath you, without bottom. You fall not as a consequence of such ambition, but in the act of ambition itself, which cuts you off from reality and love.

So when we see Satan, with all those words that suggest how high he is seated, and how high he aspires, we are made to know to what depths he has fallen and continues to fall. It is brilliant, poetically, theologically, and even psychologically. He is insatiable in his aspirations, which are vain, empty. He is trying to fill himself with nonexistence. Such, we might say, is the height of folly.

High on a throne of royal state, which far Outshone the wealth of Ormuz or of Ind, Or where the gorgeous east with richest hand Showers on her kings barbaric pearl and gold, Satan exalted sat, by merit raised To that bad eminence, and from despair Thus high uplifted beyond hope, aspires Beyond thus high, insatiate to pursue Vain war with Heaven, and by success untaught, His proud imaginations thus displayed.

Word & Song by Anthony Esolen is an online magazine devoted to reclaiming the good, the beautiful, and the true. We publish six essays each week, on words, classic hymns, poems, films, and popular songs, as well a weekly podcast for paid subscribers, alternately Poetry Aloud or Anthony Esolen Speaks. Paid subscribers also receive audio-enhanced posts and on-demand access to our full archive, and may add their comments to our posts and discussions. To support this project, please join us as a free or paid subscriber. We value all of our subscribers, and we thank you for reading Word and Song!

Listen to this episode with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Word & Song by Anthony Esolen to listen to this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.