When I was discussing our Word of the Week, mood, I had occasion to recall Plato’s powerful and illuminating metaphor for the soul, as a charioteer with his brace of horses, one wayward and sulky, representing the appetite, and the other noble and almost rational, representing what in English we don’t really have a single word for — courage, aspiration, high-mindedness, zeal, spirit. The charioteer, who represents reason, must rely on those horses, because without them he doesn’t go anywhere; but without him, the horses themselves don’t go anywhere either, because they have no direction. And now I think that there’s something special about the relationship between the man and the horse, which is rather like the relationship between man and man’s best friend, the dog, when man-and-dog are hunting, herding, tracking, or doing as one any of the thousand things that that wonderful creature the dog has agreed to learn how to do.

I’m speaking here only from observation, because I’m not a horseman. Neither was my father. When he was dying, one of my uncles asked him if there was anything he regretted not having done. My father, a very good man, just said that there was one thing, namely that he’d never learned to ride a horse. I now take it that my father sensed something about that particular thing: that the horse-and-man, when they are on the trail, are really together, and that the horse isn’t just a tool to the rider, and the rider isn’t just an exterior spur to the horse. It’s as if — and we see this in dogs, don’t we? — that the horse were trembling on the verge of personality, somehow, as far as it is possible for him, understanding that he is doing something good and fine. It’s as if the horse partook of the intention of the rider, and a rider who understands the horse’s feelings will feel in turn the obedient power of the horse.

Our Poem of the Week, “How They Brought the Good News from Ghent to Aix,” is one of those that are great for kids, because all its meaning and its power are right out in front, and you don’t have to have studied history or philosophy or literature to get what’s going on. The poet Robert Browning sets for us an imaginary situation of great urgency. Three couriers are riding at breakneck speed to get from Ghent to Aix to tell them the news “which alone could save Aix from her fate.” It’s the speaker, whose name we aren’t told, and his fellows Dirck and Joris, but the real hero of the poem, and the name we hear most often, is the speaker’s horse Roland. Of course it ought to be Roland! — named for the hero of that gloriously colorful and hearty French epic The Song of Roland, which turns a legendary defeat, the ambush by Saracens of the rear-guard of Charlemagne’s army at Roncesvalles (that’s a narrow pass through the Pyrenees from Spain into France), into a song of triumph. But again, you don’t have to know that business about Charlemagne and Roland to be swept along with Browning’s poem.

For the galloping sound of it all, “How They Brought the Good News” is a great example of how a poet can deliver his meaning not just by the idea of a word but by its physicality. Think of Rossini’s famous William Tell Overture, the theme music for the old radio and television show, The Lone Ranger. How can that music not be for riding horses into battle? So then, Browning chooses for his meter the anapest, da-da-DUM, which, because it has three syllables and not two, tends to speed up the voice, just as eighth-notes in a song do. The idea is that the mind’s ear picks up on how many strong stresses there are, and then if you’ve got an extra syllable between them, you end up pronouncing those twice as fast. By the way, for the first foot in such meter it’s allowable to simply have da-DUM. This is the meter Dr. Seuss uses in his rhyming poems for children: “Every WHO down in WHO-ville liked CHRIST-mas a LOT.”

That’s not all, of course — Browning chooses words that sound like the hooves of galloping horses, and that make us feel the high-hearted urgency of the riders, going all out to get to Aix in time to deliver their news. So the drama is one of speed, racing against time, and in the dark, too, but it is also the drama of the man and the horse, that good obedient courageous horse, and the key moment comes when the rider whispers the “pet name” to Roland, a name that’s private between him and Roland — and Roland responds. Well did the citizens of Aix vote their best wine as a reward to him who brought that good news — to Roland the horse!

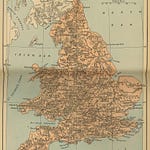

I SPRANG to the stirrup, and Joris, and he; I galloped, Dirck galloped, we galloped all three; ‘Good speed!’ cried the watch, as the gate-bolts undrew; ‘Speed!’ echoed the wall to us galloping through; Behind shut the postern, the lights sank to rest, And into the midnight we galloped abreast. Not a word to each other; we kept the great pace Neck by neck, stride by stride, never changing our place; I turned in my saddle and made its girths tight, Then shortened each stirrup, and set the pique right, Rebuckled the cheek-strap, chained slacker the bit, Nor galloped less steadily Roland a whit. ’Twas moonset at starting; but while we drew near Lokeren, the cocks crew and twilight dawned clear; At Boom, a great yellow star came out to see; At Düffeld, ’twas morning as plain as could be; And from Mecheln church-steeple we heard the half-chime, So Joris broke silence with ‘Yet there is time!’ At Aerschot, up leaped of a sudden the sun, And against him the cattle stood black every one, To stare through the mist at us galloping past, And I saw my stout galloper Roland at last, With resolute shoulders, each butting away The haze, as some bluff river headland its spray. And his low head and crest, just one sharp ear bent back For my voice, and the other pricked out on his track; And one eye’s black intelligence,—ever that glance O’er its white edge at me, his own master, askance! And the thick heavy spume-flakes which aye and anon His fierce lips shook upwards in galloping on. By Hasselt, Dirck groaned; and cried Joris, ‘Stay spur! Your Roos galloped bravely, the fault’s not in her, We’ll remember at Aix’—for one heard the quick wheeze Of her chest, saw the stretched neck and staggering knees, And sunk tail, and horrible heave of the flank, As down on her haunches she shuddered and sank. So we were left galloping, Joris and I, Past Looz and past Tongres, no cloud in the sky; The broad sun above laughed a pitiless laugh, ’Neath our feet broke the brittle bright stubble like chaff; Till over by Dalhem a dome-spire sprang white, And ‘Gallop,’ gasped Joris, ‘for Aix is in sight!’ ‘How they’ll greet us!’—and all in a moment his roan Rolled neck and croup over, lay dead as a stone; And there was my Roland to bear the whole weight Of the news which alone could save Aix from her fate, With his nostrils like pits full of blood to the brim, And with circles of red for his eye-sockets’ rim. Then I cast loose my buffcoat, each holster let fall, Shook off both my jack-boots, let go belt and all, Stood up in the stirrup, leaned, patted his ear, Called my Roland his pet-name, my horse without peer; Clapped my hands, laughed and sang, any noise, bad or good, Till at length into Aix Roland galloped and stood. And all I remember is, friends flocking round As I sat with his head ’twixt my knees on the ground; And no voice but was praising this Roland of mine, As I poured down his throat our last measure of wine, Which (the burgesses voted by common consent) Was no more than his due who brought good news from Ghent.

Note: Paid Subscribers have access to our full archive, on demand. We greatly appreciate your support and encouragement as we continue to reclaim the good, the beautiful, and the true!

Share this post