The link to the online video has been fixed. Thank you for your patience.

We’ve featured the work of Alfred Hitchcock several times for our Film of the Week, so I don’t suppose it will surprise our readers to find him here again. You may know that Hitch never won an Oscar, though he did get a nomination or two, and it may be that his phenomenal success in one feature of film-making dulled people’s perceptions of some more important things that he was doing. He was called the master of suspense, and he certainly was that, but while everybody was focusing on Cary Grant trying to hold on to Eva Marie Saint as they were picking their uneasy way over presidential faces on Mount Rushmore, in North by Northwest, or Teresa Wright trying to escape from the clutches of her wicked uncle in Shadow of a Doubt, or Bob Cummings grasping the spy Norman Lloyd by the fingers as he dangles over the side of Miss Liberty’s crown in Sabotage, they forgot that what made Hitchcock’s stories most powerful was his staging of moral problems, usually facing an otherwise ordinary person caught up in a terrible crisis not of his making. That is, he shows the heroic moral courage that may lie hidden in the human heart, requiring the situation to reveal it, even to the person himself.

We are, then, full of possibilities, secret to the world and to ourselves; or we may say that Hitchcock dramatizes man, walking along a precipice, usually unseen, but still there. Or each moment is like a corner in time, and great things may depend upon whether we make that apparently small turn to the good or to the bad. I’d say it’s what divides Hitchcock’s movies from those of Steven Spielberg, or at least from such movies as Jaws. The shark may have us at the edge of our seats, but we can avoid him by not going swimming; there’s no moral force to the monster. We can’t avoid what Hitchcock shows us, because it is the warp and woof of human life.

Now, there is an extraordinary situation in I Confess, but it’s what begins the film: the event has already happened. That is, the caretaker at a church and rectory in Quebec City, in a burglary gone awry, has murdered a rich man. The man had hired him to work as a gardener. But this caretaker, Otto Keller (O. E. Hasse), has confessed to the crime — only, not to the police. He has confessed it to Father Michael Logan (Montgomery Clift), in the confessional. Of course, for Father Logan to give him absolution, Keller must confess to the crime in a public way; that’s the obvious restitution that the situation requires. But even so, the priest is not permitted to broach the secret. In American law, in many jurisdictions at least, the priest-penitent privilege is upheld, not just for Catholic priests but for all clergymen; the idea is that we want to keep sacrosanct the possibility that people burdened with guilt will seek out spiritual counsel, without fear of enforced revelation.

Father Logan is also bound by the rules of the Church, as Hitchcock’s audience no doubt knew very well. A priest who repeats what is said by a penitent, or who deliberately leaves clues leading to the discovery of what is said, is guilty of a terrible sacrilege; the sanctions and the punishments, which I won’t get into, are remarkably severe. The thing is, Keller knows this, and his “confessing” to Father Logan becomes a part of his strategy to get away with the crime by casting suspicion upon Logan himself. Father Logan cannot defend himself except by breaking his vow. And the chief of police, Inspector Larue (Karl Malden, terrific as always), discovers that Logan had the means, the opportunity, and, he believes, a very strong motive for wanting the murdered man out of the way. This shadowy motive has something to do with the socialite Ruth Grandfort (Anne Baxter), a woman whom Father Logan once loved, but that was before the war and before he decided to devote his life to God. Blackmail, you see.

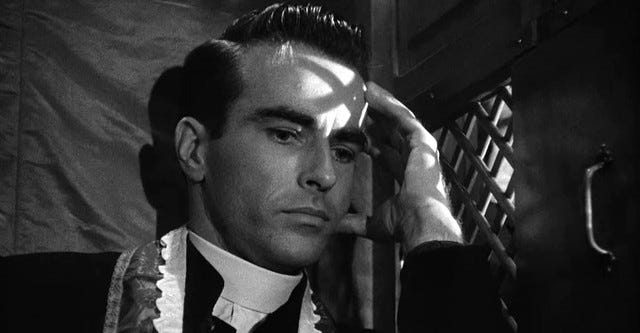

So then, what do you do? What can you do? Father Logan’s reputation is in a shambles. He would like to protect Ruth, but he cannot, not without breaking his vow. He cannot do the obvious, which would be to put the police on the lead of finding the true murderer. Montgomery Clift was himself a man beset by inner demons — he did not know much happiness in his life. He once said that when he needed to play the part of someone in a mad and frothing rage, all he needed to do was to call to mind the image of his father. He had a most expressive face, not hard-chiseled like John Wayne, not sly and ominous like Robert Mitchum, but strangely vulnerable, though he was by no means slightly built. Opposite him we find the hard-driving, “rational” and therefore not always perspicacious Inspector, whom Karl Malden plays perfectly, and Anne Baxter, who could play as well as anybody in those days the proud woman, alternately smoldering and cool — think of her Nefretiri in The Ten Commandments. This is a movie for people who appreciate the possibilities of what is not said, and what is not done, or the secret rooms in the human soul.

The on-location shooting in old Quebec City is a viewing bonus. Two years after I Confess, Hitchcock took his crew to northern Vermont - about 200 miles from Quebec City - to direct the beautiful autumn scenery in The Trouble With Harry.

I love this movie and have watched it nearly half a dozen times. Thanks for your insights