“Seek,” says Jesus, “and you shall find.” The kingdom of God, he says, may be likened to a man who was seeking fine pearls, who when he found one pearl of great price, sold all that he had to obtain that pearl. Here’s the thing about the seeking that Jesus enjoins upon us: we can be confident of finding, not because we’re lucky, but because God is seeking us: he calls us by name; he stands ready at the door; he came among us in the flesh to lead us home.

When I read, for Word and Song, about the lives of poets, composers, and artists of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, they sure do seem to have been on the move at an early age. Put it this way: the spirit of the quest, the adventure, was strong in them, and I don’t mean that they ended up sailing over the world or hunting lions in the Serengeti. It may sound paradoxical, but the stronger your faith, the more confident you will be when you set forth, and the more likely you will be to set forth in the first place. Only people who believe in the Holy Grail go out to seek its mysteries.

So then, imagine a ten year old boy applying for admission to the Royal Academy of Music, in London. Read that sentence again! The year was 1826, and the boy’s name was William Sterndale Bennett. He became one of the most important teachers and promoters of classical music in England in the nineteenth century, and an accomplished performer and composer in his own right. He must have had quite a talent — at least, Mendelssohn thought so, and Mendelssohn was one of those happy souls who seem never to have been afflicted with even a trace of envy, so that he could and did admire excellence and grace wherever he found it. And Mendelssohn sought excellence and grace, and was delighted to find it; he was like Antonin Dvorak in that way, combing America and hearing the strains of the Negro spirituals for the first time.

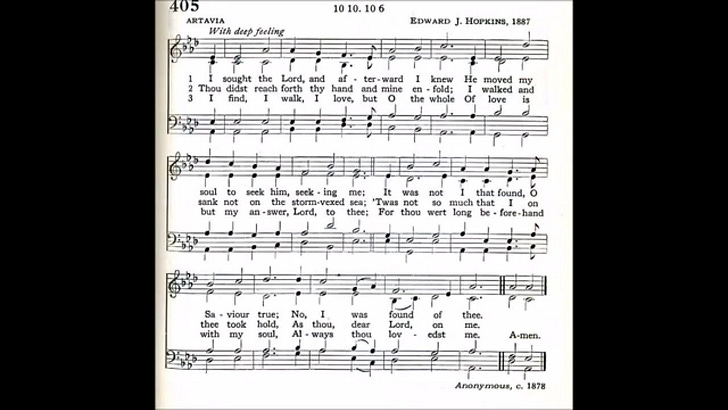

Perhaps some of Mendelssohn’s habit of admiration entered Bennett’s own soul, since it was he who did more than anyone to bring Bach to the attention of English audiences. In 1854, Bennett, one of the founders of the new Bach Society, conducted the first English performance of Bach’s Saint Matthew Passion. The organist — the most important of the musicians in that titanic work — was Edward J. Hopkins, the composer for the melody Artavia, our melody of choice for the Hymn of the Week, “I Sought the Lord.”

Hopkins himself was an early seeker, too. In 1834, the people in charge of music at Saints Peter and Paul, in Mitcham, a borough in the southwest of London, were looking for a new organist, so they held a blind audition, meaning that they did not know who was at the organ, nor, apparently, were they introduced to the auditioners beforehand. Edward Hopkins was then 16 years old. He had his heart all in it. He won the audition, but when the organizers saw him, they blanched. “He’s only a boy!” they said. But Hopkins had a friend in a high place: the organist at Westminster Abbey, for whom he substituted at times. Well, if you are good enough for Westminster, you are good enough for Mitcham. And Hopkins, like Bennett, who was but two years his senior, began a long and distinguished career in music. In his case, he not only played the organ: he studied the organ and its instrumentation; he built organs; he wrote about them. Organs were not mass produced. You did not so much choose an organ for your church, as that your church — its acoustics, its space, its architectural opportunities and limitations — determined the dimensions and the characteristics of the organ that would be built for it; how many manuals the organ would have, how many ranks of pipes there would be, what kinds of sounds they would be formed to make, and where they would be placed to best advantage.

We don’t know who wrote “I Sought the Lord,” though lately it has been attributed to Jean Ingelow (1820-1897), a prolific Victorian poet. The mood is right for her, as far as I can judge by one of her long poems, “Honors,” written in exactly the same meter and with the same rhyme scheme as is our hymn. The main speaker in “Honors” is a young scholar seeking God in an age of doubts. His answer comes from a friend, who says that he too once sought for God, but in the wrong places: “I have aspired to know the might of God, / As if the story of His love were furled.” There’s the key. The anonymous author of that great work of medieval mysticism and the life of prayer, The Cloud of Unknowing, says that God cannot be grasped by the intellect, but only by love. That’s not to disparage the intellect, but to emphasize that God is a person — is Personhood itself; and we cannot know even a human person unless we love.

But here’s the thing with persons: they act, they can love. A theorem can’t act. A law can’t love. Good laws can help to make us fair and decent people, or at least help to keep us from becoming very bad people, but they can’t make us into persons. When it comes to the soul and God, all the initiative is on His side. If God left us to ourselves, we would seek forever and never find, or we would cease to seek, and that would be as if we had sealed ourselves up in a prison — comfortable, maybe, but still a prison. But God is beforehand with his mercy, and that’s a good thing for us. He is here, even at the gates.

Given the content of today’s essay, we had hoped to find a good organ rendition of our hymn, with the tune Artavia, perhaps sung by an excellent choir. We found only this demonstration of a simple piano version of Artavia, and have included it here for you to listen to, along with the words, below.

I sought the Lord, and afterward I knew He moved my soul to seek him, seeking me; It was not I that found, O Savior true; No, I was found of thee. Thou didst reach forth my hand and mine enfold; I walked and sank not on the storm-vexed sea; 'Twas not so much that I on thee took hold, As thou, dear Lord, on me. I find, I walk, I love, but O the whole Of love is but my answer, Lord, to thee; For thou wert long beforehand with my soul: Always thou lovedst me.

I never heard this hymn before, but when I read the title my mind automatically supplied the next line a la The Crickets, “but the Lord won.”