“I, too, dislike it,” said Marianne Moore at the beginning of her own poem about poetry, and I’m afraid that I’d say much the same thing about most of the work that she and her modernist colleagues produced. I don’t mean to sound harsh, but first they gave up singing for saying, and then their successors often gave up saying for grunting, or for a sort of intellectual posing which is just another kind of grunting, the kind you do at a faculty wine and cheese affair to show other people that you, too, can be dull and fashionable all at once, and have nobody understand what you’re saying.

But directness and simplicity in verse can be great virtues, and the best poets avail themselves of it. “O how unlike the place from whence he fell,” says Milton, comparing where Satan is now to where he used to be. One sentence, one line, and that’s that. “’Tis new to thee,” says the elderly Prospero, sadly, when his daughter Miranda, marveling at the variety of human beings that she on their desert island has never beheld before, is overcome with wonder. “Uneasy lies the head that wears a crown,” says Henry IV, who got that crown by shady means, and has not found it all he had hoped for. “A little learning is a dangerous thing,” says Alexander Pope, and don’t our current elites prove him right!

And what if you’re a preacher of the word of God? Don’t you then work under a special duty, to be clear, to have people understand you and be moved by what you say? Yet, if you are an artist too, those same divine things warrant your devotion, your intelligence, your labor, your sweat. The trick, then, is to be at once a great artist and a clear and cogent preacher; to be most artful in your artlessness, to lead people by what they can readily understand into mysteries that you yourself cannot claim to understand or even to see more than a glimmer of.

So, in his poem “Jordan (I)” (it’s the first of two by that title), the priest and poet George Herbert, with an art that is both subtle and simple, claims a right to a kind of poetry that dispenses with the “fictions and false hair” that overburden the baroque, and that are often only a cover for what is coarse and slovenly. No nightingales in his poems, no “purling streams,” no “sudden arbors,” no “winding stair.” Herbert’s the poet, note well, who can write a poem whose lines, read on the diagonal with one word per line, spell out “My life is hid in Christ who is my treasure.” He’s the poet who can craft his verse in “Easter Wings” to look just like the wings they describe. He’s capable of many an intricate turn! But it is never to show off. It’s always to delight and to instruct. And I say that George Herbert is not just the greatest religious lyric poet in English. I say he is the greatest of all our lyric poets, religious or not.

Our poem here is but three stanzas long, the first two made up of rhetorical questions, the most powerful of which, I think, is this: “Is there in truth no beauty?” That’s my emphasis, there. Must we always have décor to distract us? Must we have the poetic equivalent of computer-generated explosions? Or frills and finery to pass for real feeling? Are no lines to pass muster, unless they bow and scrape, not before a true king and his throne, but to a mere “painted chair”? May the streams never be those true streams of living water that the psalmist longs for? Must they always be there just to “refresh a lover’s loves,” a line that is as dull, deliberately, as is the stale lover in a stale love poem, or as we ourselves become, when a merely human love is untouched by the divine?

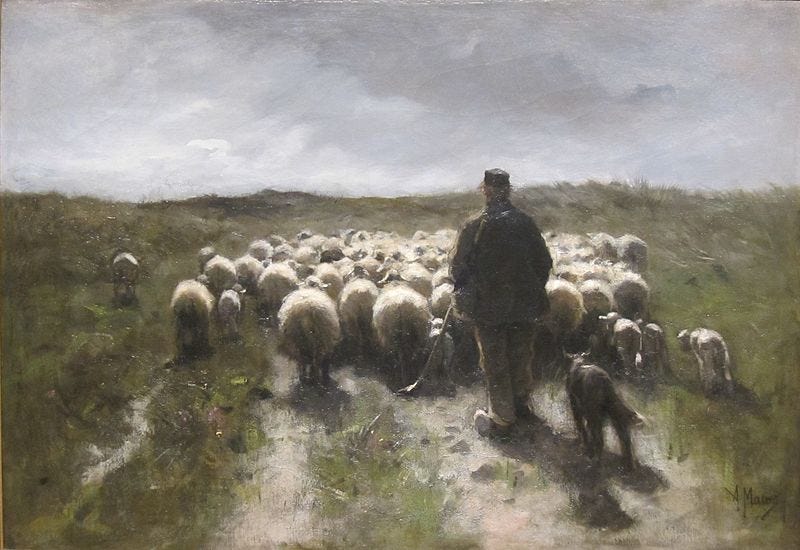

No, says Herbert, for “shepherds are honest people,” meaning of course shepherds of the Lord’s flock, but also plain men with no political pretenses. Let others riddle if they want. Let them “pull for prime,” gambling at the card game primero, like drawing to an inside straight in poker. Those poets may do as they please, so long as they don’t punish him with “loss of rhyme,” when he says, straight out, “My God, my king.” Thus in the final line of the poem, form and meaning converge – and there is no more to say.

Who says that fictions only and false hair

Become a verse? Is there in truth no beauty?

Is all good structure in a winding stair?

May no lines pass, except they do their duty

Not to a true, but painted chair?

Is it no verse, except enchanted groves

And sudden arbors shadow coarse-spun lines?

Must purling streams refresh a lover's loves?

Must all be veiled, while he that reads, divines,

Catching the sense at two removes?

Shepherds are honest people; let them sing;

Riddle who list, for me, and pull for prime;

I envy no man's nightingale or spring;

Nor let them punish me with loss of rhyme,

Who plainly say, my God, my King.

Share this post