When she was an undergraduate, our daughter Jessica took several courses from a wonderfully wise linguistics professor, Elaine Chaika, who was also, as we are, a great lover of dogs. Elaine said that man's best friend really was exactly that. The domesticated dog was smart enough to cull healthy animals from a wild herd, and obedient enough — and obedience also requires brains — to leave them for the masters. Of course, that meant too that the dogs were smart enough to understand that they would be fed and cared for. They had their special work in the human pack. Our dog Jasper of happy memory thought of himself as my aide-de-camp. He loved everybody, but he decided early on that his job was to take direction from me. In any case, it seems that the smartest dogs of all are those that have to take care of sheep, those harmless and brainless creatures, which the sheep dogs treat in part as ornery rams, and in part as little lambs quite incapable of caring for themselves. If you’ve ever seen sheep dogs in action, you’ll understand why it’s really hard to imagine how people could ever herd sheep without the dog’s help.

Back in March, we featured an excellent film about the bond between a child and an animal, The Black Stallion, and now it’s time for the great granddaddy of all such films, Lassie Come Home. Is there any native speaker of English who hasn’t heard of Lassie? When I was a boy, the first present I ever asked for from my parents was a dog, and they got me one which I picked out myself, a collie puppy I named Duke. I was seven years old. When we lost Duke six years later, probably shot by one of our neighbors, I got another collie and named her Duchess, of course. The dogs were smart, and all my cousins and aunts and uncles loved Duchess. They’d beg us to let them take care of her if we were going away. Collies were pretty common pets back then.

It all came from a 1940 children’s novel, Lassie Come Home, which MGM wasted no time in turning into a feature film in bold Technicolor, with all the gorgeous greens and blues of Scottish downs and Scottish skies, and the bright golden-brown and white of Lassie herself. You may know that Lassie was played by a male dog — Pal, who was a bit bigger than the female dog the producers were at first considering, and who could do the strenuous stunts with a little more aplomb and a little less risk and exhaustion. Lassie, that is to say Pal, is one of three dogs with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame: Lassie, Rin-Tin-Tin, and Strongheart — one collie and two German shepherds.

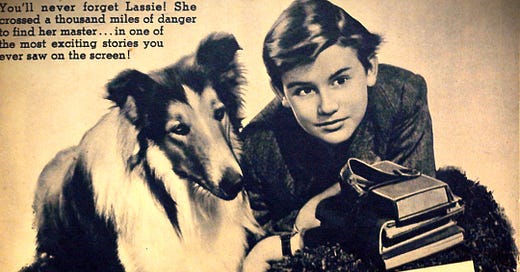

The story of Lassie Come Home combines three plots that are common in human folklore, and that appeal immediately to people of all cultures. One is that of the animal bound in love to a certain person, especially a child. In Lassie Come Home, the child is a Yorkshire schoolboy, Joe Carraclough (played by Roddy McDowall, at the time the most celebrated child actor in English films, from his wonderful portrayal of young Huw in How Green Was My Valley, the Oscar-winning Best Film for 1941). The other plot is that of the dignity of the poor, set against the power and the strange hard-heartedness of the rich, even when the rich aren’t particularly malicious. For the Duke of Rudling (Nigel Bruce, who played the comical Dr. Watson in a series of Sherlock Holmes films) wants Lassie for his own. He offers to buy her, and his offers are refused, until hard times hit the Carracloughs, and Mr. and Mrs. Carraclough (Donald Crisp and Elsa Lanchester) are finfally reduced to selling the dog. The Duke takes Lassie with him to London. But Lassie’s heart is not with him. She gets free, and the film is about how she manages somehow to get from London all the way back home to the schoolyard where she’s used to waiting for Joe. And of course, plenty of obstacles, human and otherwise, threaten to get in her way, but there are also human helpers too — see the very young Elizabeth Taylor as one of them, and the charming elderly Dame May Whitty as another.

Did I say there were three fundamental plots to Lassie Come Home. The other one we featured here last week, in The Trip to Bountiful: it’s going home. It’s Odysseus, trying so hard to return to Ithaca, that rocky place he loves not for its beauty or its fruitfulness, but because it is his place, his home. It’s the yearning of the Prodigal Son, after his wandering into folly and dissipation and loneliness and hunger. We call it homesickness, the Germans call it Sehnsucht — the yearning to see again; in Scripture, we find it when the children of Israel, in exile, sit and weep by the waters of Babylon. The older I grow, the stronger and more persistent my memories of my youth become, and I see the faces of people who long ago have left this world. Our faith looks ahead to the true and ultimate home, where all that was good and beautiful in our lives will be restored, or rather, made new, assumed into glory.

Note: Our full archive of over 1,000 posts, videos, audios is available on demand to paid subscribers, but our most recent free content remains open to all subscribers for some weeks after publication. We know that not everyone has time every day for a read and a listen. So we have built the archive with you all in mind. Please do browse, and please do share posts that you like with others.

Thank you, as always, for supporting our effort to restore every day a little bit of the good, the beautiful, and the true.

Even knowing the happy ending, I find it hard to watch this movie because of the sad parts. Sean the Sheepman videos, on the other hand, are nothing but happiness. I enjoy watching both the dogs in action and Sean’s love for them.

Sheep dogs never cease to amaze me. I swear they could herd cats, if anyone thought to give it a try.