I have been putting the finishing touches on a book-length poem made up of 144 poems, called The Twelve-Gated City, after the heavenly Jerusalem that John saw in a vision, in Revelation. Our excerpt today comes from the end of the first of 33 dramatic monologues or dialogues. This one, as I’ve imagined it, is spoken by Moses, a very old man, on the top of Mount Pisgah, just before his death. You may remember that the Lord punished Moses for his doubtfulness, when the prophet struck the rock not once but twice, and there came forth a spring of water for the thirsty people. What would Moses think about, as he sat on that mountain and watched the people below, in their cheer and celebration? What would his final instruction to Joshua — Yehoshua — be?

Deuteronomy 34: 1-4 And Moses went up from the plains of Moab unto the mountain of Nebo, to the top of Pisgah, that is over against Jericho. And the Lord shewed him all the land of Gilead, unto Dan, And all Naphtali, and the land of Ephraim, and Manasseh, and all the land of Judah, unto the utmost sea, And the south, and the plain of the valley of Jericho, the city of palm trees, unto Zoar. And the Lord said unto him, This is the land which I sware unto Abraham, unto Isaac, and unto Jacob, saying, I will give it unto thy seed: I have caused thee to see it with thine eyes, but thou shalt not go over thither.

I often think that if we could understand the first two commandments (or three, depending on how you number them) that the Lord gave to Moses, we would understand everything about how we must be as the people of God, and we would gain a wisdom that could make sense of all the world and our place in it. It’s not that Moses himself says he understands it. He doesn’t — how could he? Only with Christ can we see the Father. But he begs the first “Jesus,” that is, Joshua, to keep those commandments regardless of whether he or anybody yet can understand why. And with pagans all around, it might be very hard for an ordinary son of Israel to understand why other people should abound in gods, but the chosen people should acknowledge only One.

My gentle brother Aaron is no more. He liked the people well, but loved them less; No more my envious Miriam and her songs. The hour draws near. I have a thing to say, Yehoshua, but I stammer, and the sun Is sloping to its den, when you must go. The rabble of gods in Canaan all have names And faces, such as men with clever hands – Like our Aholiab and Bezaleel – Might whittle from a stump of wood, or stone, To be familiar on the mantel-piece, An ally, or a bargainer in bad times. But when I asked, “Who shall I say has sent me?”, He from the fire who called Himself the God Of all our fathers, God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, God of seed and flesh, Sounded the Name above all other names Because it is none, nor may it be uttered. Promise, Yehoshua – by that holiest flame That purges as it burns, by that dread earth I dared not set my foot upon – swear, swear To the old man you shall not see again, You will keep those commandments traced in stone By the invisible finger of our God, Even those impossible to understand, Never to own a neighborhood of gods, Never to hold Him captive in a face, Never to smudge and smear the holy Name As if it were a shekel in your bag – Three several laws, but one, as He is one. Somehow, I could not tell you if I knew, On these bewildering ordinances depend Earth and the heavens and all the hosts therein. Let Israel not grow old in her conceit! Let not the river of obedience sink Into the sands of slavery and self-will. Go now, my good lad. I am not alone, And if you see a misting in my eyes, Think I am standing on a shore at dawn When all the east is silence, life, and fire. More, ever more – I go to seek His face And hearken to the music of His name. One kiss, Yehoshua. Yours is now the time. Go lead our children to the Promised Land.

Dare I wonder at and explore and peek around corners and poke about in the crevices of the Esolen mind with its devices and designs to ask if the excerpt here, being part of the first monologue/dialogue, might be associated with (given the book's title and the rooted factors of that ominous number 144) one of the twelve stones of the twelve foundations of the heavenly Jerusalem? And, if so, even hazard a guess at which stone it might be? The stone of the first foundation (and apparently of which the entire wall is based) is Jasper (also he of fond memory). Or am I, like the dwarves in the mines of Moria delving too deep into the mountain's roots with my machinations and risk uncovering a balrog of misconception? :-)

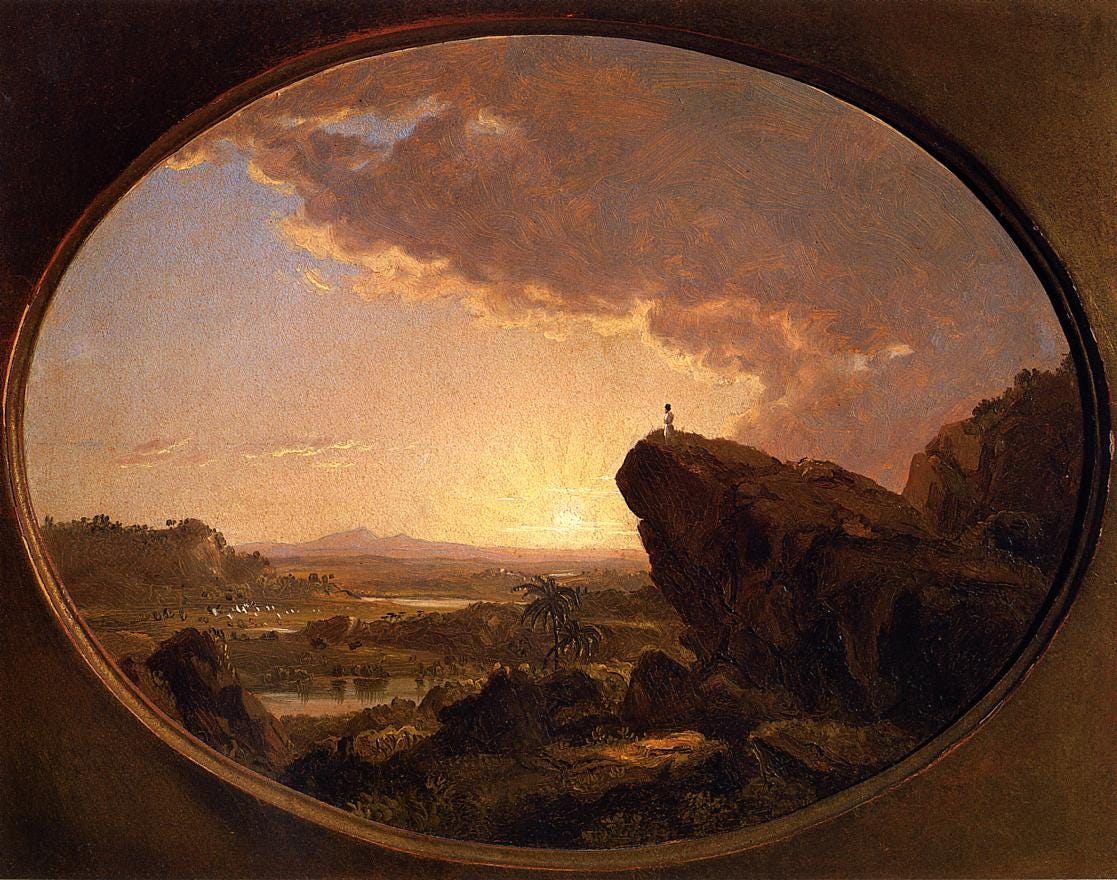

But on to the poem itself (or excerpt from) above: Having read it over several times now, a single word "distance" rings through my head at the imagery and thoughts of Moses described (and suggested and amplified by the beautiful accompanying painting, certainly), even though that word does not actually occur in the excerpt. And it seems to me that that is pretty much what Scripture conveys to us about God over and over throughout Old and New Testaments. But not distance as merely a separation of the "end goal" from the observer (though certainly that too), but also inclusive of all that lies between, ie, almost the "distance" itself -- IF, and only if, that between-ness does not become "all there is" to the distance (nor any sort of pantheistic implication either, of course), as the lines of your excerpt warn,

"...Never to own a neighborhood of gods,

Never to hold Him captive in a face,

Never to smudge and smear the holy Name

As if it were a shekel in your bag..."

Rather, I guess, that "distance" itself, and the awe it produces in us, I sense is more of a "pointer" to that goal, just as a road to a city is not the city itself, but a way of arriving at the city. I'm reminded much of perhaps my favorite passage from C. S. Lewis' book "That Hideous Strength," where Jane Studdock is taking a train from the fog-enveloped town of Edgestow up to St. Anne’s and she is enchanted by the change of scenery as the train rises out of the fog to reveal the landscape above in the hills:

-------

"She took a deep breath. It was the size of this world above the fog which impressed her. Down in Edgestow all these days one had lived, even when out-of-doors, as if in a room, for only objects close at hand were visible. She felt she had come near to forgetting how big the sky is, how remote the horizon."

-------

Ah well, will be awaiting its publication with anticipation and I look forward to seeing other excerpts in the remaining Fridays of Lent!