Our back-to-school discount is still on at Word & Song, good for new paid and upgraded subscriptions as well as gifts (for the students, teachers, homeschoolers, and just about anyone who might like our magazine).

I am typing these words early in the evening, in the northern hemisphere, just after fall has arrived and the days have begun to grow shorter. It’s pretty noticeable. When I was a boy, all our Little League games began at 6 PM sharp, and that was fine, because it was summer, and the sun wouldn’t set for another two hours at least. But as I look out the window now, I know that it’s much too dim for baseball, unless of course you’re playing under the glare of big electric lights, but our field didn’t have any, and we didn’t need any. We had light, the first of creation, “offspring of Heaven first-born,” says Milton.

Our Hymn of the Week is one of the earliest Christian hymns we still possess, perhaps even the very earliest. It’s known by its first words in Greek, Phos hilaron, which the English poet Robert Bridges happily rendered as O Gladsome light. I once knew a Presbyterian minister who would call for offerings during the Sunday service by echoing the single use of that adjective hilaro[n] in the New Testament. It’s from Saint Paul, reminding the Corinthians that “God loves a cheerful giver,” only Reverend Miller put it that “God loves a hilarious giver.” You can imagine the light in the face of such a giver, not glum, not self-important. Some people, when they smile, look as if they’re baring their teeth to keep you at a distance or to intimidate you: like Mr. Carker, that Machiavellian schemer of many teeth, in Dickens’ Dombey ad Son. But don’t we say, in English, that someone who is cheerful or happy has light in his eyes? The psalmists sing often of the light of God’s countenance, and it was only natural that whoever wrote this early hymn, which the Orthodox chant at the fall of the day, should associate it also with the light we see above us. One thing you’ll notice about pretty much any hymn written before 1000, if not 1500: it’s likely to focus entirely on God, not on the feelings of the singer. The hymns are vast in scope; cosmic, you might say.

It’s a perfect hymn for Bridges, our translator. While other artists in the early twentieth century were picking through the rubble of a fallen civilization, and while some of them sought to turn grime into a virtue, Bridges, near the end of his long life, in his epic Testament of Beauty, called Beauty “the eternal Spouse of the Wisdom of God, / And Angel of his presence through all Creation.” He imagines the sheer exuberance of song in the nightingale, far more than necessary to attract a mate. Everywhere around us, and in the evening too, we find glory. There is a bush I can see from the window too, whose name here in North America would have pleased Bridges: the burning bush. It’s called that because its leaves in the fall turn a bold and bright red. Of course, the name refers to the burning bush in Exodus, which Moses approached, because though it seemed to be blazing with fire, it was not consumed. And it was from that fire and that bush alive with burning light that God spoke His unutterable Name, the Name that is no name.

How do you behold the light of the Father’s face? In Jesus Christ: and that’s what the author of the hymn holds forth for us. In the Son of God we see the Father, “whom else no creature can behold,” says Milton; and to all who call upon him, he is mild, and his countenance beams with light. Here is what the ancient Greek says, in the literal translation used for prayer by the Orthodox Church in America:

“O Gladsome Light of the Holy Glory of the Immortal Father, Heavenly, Holy, Blessed Jesus Christ! Now that we have come to the setting of the sun and behold the light of evening, we praise God Father, Son and Holy Spirit. For meet it is at all times to worship Thee with voices of praise. O Son of God and Giver of Life, therefore all the world doth glorify Thee.”

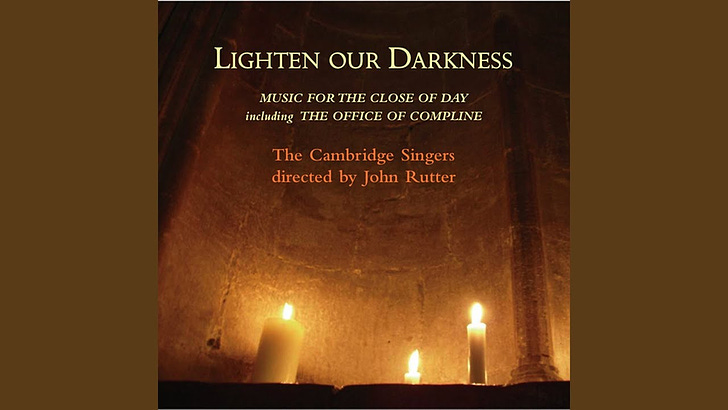

Here is our Hymn of the Week beautifully sung by the Cambridge Singers. Note especially the lovely changes John Rutter rings on the melody in the second verse, to return quietly and happily to the initial melody as the hymn concludes. Bravissimo.

O Gladsome light, O grace Of God the Father's face, The eternal splendor wearing; Celestial, holy, blest, Our Savior Jesus Christ, Joyful in thine appearing. Now, ere day fadeth quite, We see the evening light, Our wonted hymn outpouring; Father of might unknown, Thee, his incarnate Son, And Holy Ghost adoring. To thee of right belongs All praise of holy songs, O Son of God, Lifegiver; Thee, therefore, O Most High, The world doth glorify, And shall exalt forever.

This is a beautiful hymn. Anglicans recite the Phos Hilaron during evening prayer. I also appreciated what you said about the focus of hymns in the early church being God, not our own feelings.

You wrote, "One thing you’ll notice about pretty much any hymn written before 1000, if not 1500: it’s likely to focus entirely on God, not on the feelings of the singer. " I agree with this 100%.