When Saint Augustine wrote his Confessions, looking back upon his young life of intellectual confusion, empty ambition, folly, and sin, he did not say to God, “Why did you not make everything perfect for me?” Do we even know what perfection would imply? He didn’t say, “Why did you not protect me from all the wrong I did?” Do we or do we not want to be the kind of creatures we are? Creatures, that is, possessed of reason, and reason, as Milton says, “is choice,” meaning that in the exercise of reason we are free to choose between the good and the bad, or the good and the better, or even between two good things to love and to foster. God wants sons, as Saint Paul would remind us, not slaves. No, instead Augustine praised and thanked God for his being alive, his senses, his tongue to speak with, his mind, and a heart that responded to love. These are immeasurable goods. A grain of dust in the deeps of space exists: and the gap between existence and nonexistence is infinite, to be bridged only by the God whose essence it is to exist, and therefore to exist necessarily, whose non-existence is a contradiction in terms, an impossibility. I exist: and I thank God for it. But I exist as a living being. And my life is more than sleeping and breathing and feeding. I have a mind and a soul, to understand and to love: there is no creature in the universe that I cannot draw near. Yet I cannot know everything there is to know about any one of them, even that grain of dust: it is also an abyss of mystery. What is true of that dust is unfathomably truer of man. If you should ever say, “I know all there is to know about John,” or if you should behave as if you thought so, you’d only show that you were being foolish. Your neighbor is the most mysterious creature you will meet today. He or she is also the most sacred.

“I believe you are right,” you may say, “but shouldn’t we thank God for what he has done for us in our lives?” Yes, certainly! But let’s not separate those things from the two most tremendous things of all: that we exist, and that God loves us. “For God so loved the world,” says the evangelist, “that he gave his only Son, that all who believe in him might have eternal life.” Our Hymn of the Week, “O Lord of Heaven and Earth and Sea,” by Christopher Wordsworth, an Anglican bishop, a prolific writer of hymns, and nephew of the poet William Wordsworth, makes those connections clear.

The poem’s stanzas are short and swift. Each is a rhyming triplet of eight syllables, followed, with one or two slight variations, by the simple and emphatic clause, “Who givest all.” That line thus binds all the stanzas together into one complete poem, and the triplets, building up energy as they proceed, are nicely punctuated by those words that complete the thought. God gives all. And lest we say that God has remained aloof in his giving, we should keep in mind that our poor attempts to love one another are but flickering sparks to the galactic fire of divine love. Saint Paul again puts it most powerfully, when he says that maybe, just maybe, one of us might die on behalf of a good man, but God has showed his love for us, in that while we were sinners, Christ died for us. He died that excruciating and humiliating death upon the Cross, crowned with thorns in mockery, and scourged so cruelly that the shards of iron and glass on the whip’s end tore out his flesh and pierced him to the very spine; he died for Pilate who washed his hands of the deed, for the thief who railed at him, for Judas who betrayed him, for the Pharisees who connived at the execution, for Herod Antipas who treated him as a circus show, for the apostles who fled; even for you and me. That, in a dramatic and terrible way, really is to give all — to give up all.

Yet there is still something surprising that the poet wishes to remind us of, when it comes to giving, and giving thanks. Our power to give is itself given by God. And this is the secret of love, a secret in plain sight, though man finds all kinds of clever ways to miss it. It is that we grow taller by kneeling; we grow richer by giving to God the giver. And after all, what can we give to God, but what he has lent to us already? The great saints knew this, and it gave to them a frolic and innocent delight in the true goods of this world, and the joy of knowing that far more awaits, so that when it appears that flower and tree and fruit will have come to dust, then to the faithful soul, casting himself upon the bounty of God, will find again all that was good in this world, raised up, transformed. That is what the poet implies in the final line of all. We will live with God.

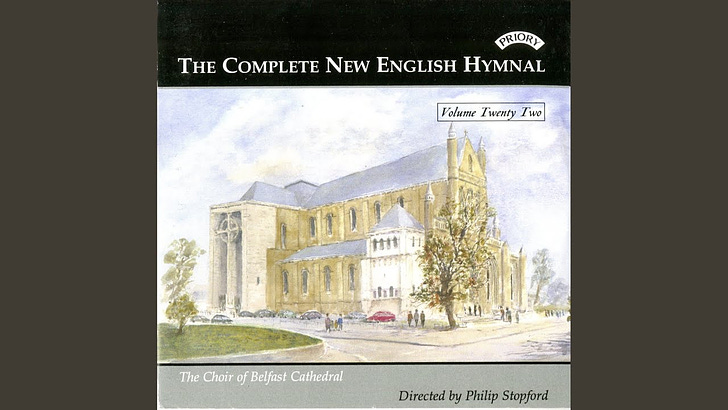

Listen to our Hymn of the Week, sung by the delightful Belfast Cathedral Choir.

O Lord of heaven and earth and sea, to thee all praise and glory be. How shall we show our love to thee who givest all? The golden sunshine, vernal air, sweet flowers and fruit, thy love declare; when harvests ripen, thou art there, who givest all. For peaceful homes, and healthful days, for all the blessings earth displays, we owe thee thankfulness and praise, who givest all. Thou didst not spare thine only Son, but gav'st him for a world undone, and freely with that blessed One thou givest all. Thou giv'st the Holy Spirit's dower, Spirit of life and love and power, and dost his sevenfold graces shower upon us all. For souls redeemed, for sins forgiven, for means of grace and hopes of heaven, Father, what can to thee be given, who givest all? We lose what on ourselves we spend, we have as treasure without end whatever, Lord, to thee we lend, who givest all. To thee, from whom we all derive our life, our gifts, our power to give: O may we ever with thee live, who givest all.