What if — let me see now — what if President Eisenhower, rolling his eyes, had had enough of British and American playwrights and poets all dewy-eyed for everything Soviet. Suppose he wrote a play of his own to send them up, exaggerating their style and exposing them to ridicule. Can you imagine it? I can’t, either!

In celebration of the three-year anniversary of Word & Song, we are extending our special on new paid, gift, and upgraded subscriptions.

THS WEEK ONLY

So the Word of the Week is silly, and we’ve got a poem today that I think is wickedly brilliant, though if you didn’t know the context, you’d read it as only silly and not a direct attack on what the author thought were crazy ideas. The author is George Canning, one of the most important British statesmen of his time, a loyal follower of William Pitt the Younger, and himself a Prime Minister too, though he died suddenly about four months into his term. Canning was a Tory, which meant, in his day, that he stood in opposition against the Whig coalition of big industrialists, aristocrats, and Jacobin ideologues. He wasn’t going for any abstract “Rights of Man,” as you’d get in Tom Paine, whom he detested, or for any spanking-new morality coming out of the German romantics. How to give a fair idea of the man? When the British conquered the island of Trinidad, Canning, then a young M.P., called for a halt to grants of land to big proprietors who would inevitably use slaves to farm them. He wanted instead that free men, both Europeans and natives, would settle there and see if new forms of agriculture could make the land really productive. Canning was later on the Englishman most responsible for seeing to it that the British cooperated with the new Latin American nations breaking free of their colonial mother-countries. He supported the emancipation of Catholics in the United Kingdom. He was a good and fair man. But if you crossed him, watch out! He could dip his pen in fire.

Anyway, the young Canning and a couple of his friends got up a magazine for about a year, called The Anti-Jacobin, and they indulged themselves in satire with abandon. Canning wrote a raucously funny play to send up romantic notions of love unmoored from marriage and the Church — all German passion and a storm of ideas out of Goethe and Schiller. Now, those men are titans of world literature, but if you can’t do a good satire of Goethe’s novel The Sorrows of Young Werther, that ultra-romantic boy who can’t deal with reality and who wastes away for unrequited love, well, you’re not really trying.

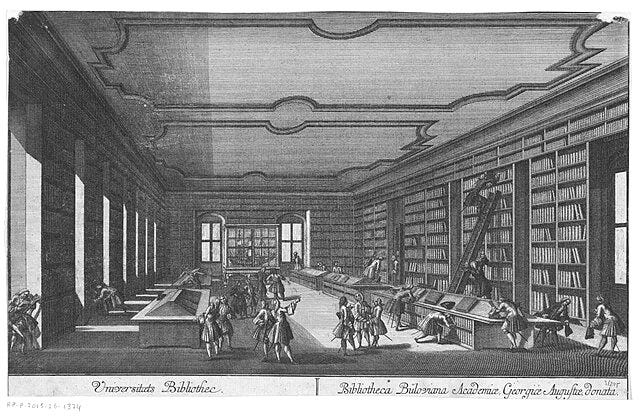

Canning’s play is called The Rovers. I can’t find the full text, darn it. Matilda Pottingen, the daughter of a law professor at — yes — the University of Gottingen, falls in love with a young student, Rogero. Dr. Pottingen doesn’t approve, so he sends Matilda far away, where she falls in love with a cavalier, Casemere. She’s going to be, as the writers of the time put it, “no better than she should be.” Meanwhile, the Duke, a vicious man responsible for the death of Rogero’s father, gets the boy confined to a dungeon, where he’s been now for more than eleven years. He’s in chains, and he is still mooning for Matilda, who is certainly not mooning for him.

I’ll give the song below with the original stage directions. Canning wrote the first five stanzas. Pitt himself, roaring with laughter when he saw them for the first time, took a pen and straight off wrote the last one. You’ve got to appreciate the three-syllable rhymes, which in English are inevitably comical (think of the two-syllable rhymes in a good limerick, such as “The Reverend Henry Ward Beecher”). And you’ve got to love the crazy line-rounding rhymes on the U-/ niversity of Gottingen! In fact, there are only two rhymes in the whole six stanza song: U and Gottingen, of all things. It’s great fun, this contrast between the pedestrian life of a law student, and the high-falutin’ emotions Rogero claims to feel, along with his super-romantic plight. It’s kind of like Elmer Fudd, as Wagner’s medieval hero Siegfried, singing “O Bwoonhiwda, you’we so wovewy,” to Bugs Bunny in a tutu.

How about it, everybody? One heads-up: “Barbs” down below is the name of a horse, sort of like “Dobbin” or “Mr. Ed.”

I. Whene’er with haggard eyes I view This dungeon that I’m rotting in, I think of those companions true Who studied with me at the U— —niversity of Gottingen— —niversity of Gottingen. Weeps, and pulls out a blue kerchief, with which he wipes his eyes; gazing tenderly at it, he proceeds— II. Sweet kerchief, checked with heavenly blue, Which once my love sat knotting in!— Alas! Matilda then was true! At least I thought so at the U— —niversity of Gottingen— —niversity of Gottingen. At the repetition of this line Rogero clanks his chains in cadence. III. Barbs! Barbs! alas! how swift you flew Her neat post-wagon trotting in! Ye bore Matilda from my view; Forlorn I languished at the U— —niversity of Gottingen— —niversity of Gottingen. IV. This faded form! this pallid hue! This blood my veins is clotting in! My years are many — they were few When first I entered at the U— —niversity of Gottingen— —niversity of Gottingen. V. There first for thee my passion grew, Sweet! sweet Matilda Pottingen! Thou wast the daughter of my tu— —tor, law professor at the U— —niversity of Gottingen— —niversity of Gottingen. VI. Sun, moon, and thou vain world, adieu, That kings and priests are plotting in: Here doomed to starve on water gru— —el, never shall I see the U— —niversity of Gottingen— —niversity of Gottingen. During the last stanza Rogero dashes his head repeatedly against the walls of his prison; and, finally, so hard as to produce a visible contusion; he then throws himself on the floor in an agony. The curtain drops; the music still continuing to play till it is wholly fallen.

Listen to this episode with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Word & Song by Anthony Esolen to listen to this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.