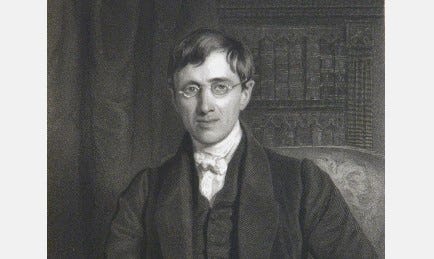

Veneration for the author of our Hymn of the Week, John Henry Newman, has come rather late for me, but has come in great force. When I was at Princeton, and then in the graduate school at North Carolina, I wanted to learn all I could about English literature from its beginnings in Anglo-Saxon to the mid-twentieth century. When I arrived at North Carolina, I still hadn’t had any course in the Victorians, whom I came to love immensely, so that was the first omission I set about to supplying. In a terrific course on Victorian literature, we read the great poets and the great prose essayists, and I confess that the fiery and often intemperate but always formidable Thomas Carlyle took my fancy. By comparison with Carlyle, Newman struck me as calm, measured, rational, pondering things carefully, all of which are virtues, but maybe not those that soonest seize attention in your youth. I now rank Newman among the greatest intellects the Christian faith has ever known, and a giant of rationality when it comes to analyzing what reason itself is, how we reason rightly, and what a humane education must do not only to direct reason but to build up those virtuous habits that reason by itself cannot build up. Newman had millennia of learning, in a variety of languages, at his fingertips, the best of what a British education had to offer, yet he wrote as a gentleman addressing his fellow men and women, just as in his published sermons he puts that immense learning to the service of speaking clearly and sweetly to all who might hear or read his words.

Before our time, it was a common enough experience to wait at the side of someone beloved, dying at home. Rich and poor knew what that was like. What then do you say to the family nearby? Or, more urgently, what do you say to the dying person? For very often, he would be conscious, or perhaps drifting in and out of consciousness. Newman decided that he would write a narrative poem, The Dream of Gerontius, to give to the faithful a vision of the event told from the point of view of the person most concerned: the dying man, “Gerontius,” a Latinized Greek name meaning, simply, “Old Man.” It’s not sentimental. Newman doesn’t shun the pain, the feeling of loneliness, the doubt (I use the word here in its etymological sense, teetering, as in a balance), the apprehensiveness. But he places it in the context of the suffering and the death of Jesus. And that’s the heart of our hymn.

Five times in the course of Gerontius’ progress from death to the beginning of his purification (I will not enter into the question of how God accomplishes that purifying), a choir of angels breaks into the narrative with a song that also tells a story. Each of the five songs begins with the same stanza: Praise to the Holiest in the height, / And in the depth be praise, / In all his words most wonderful, / Most sure in all his ways!” We’re accustomed to thinking of God as the Most High, but perhaps less accustomed to thinking of Him as the Most Deep, most intimate, “nearer to us than we are to ourselves,” as Augustine says. The story of the Son of God, come to suffer and to die for the very sinners who nailed him to the Cross, which is to say, to suffer and to die for us, is at once high, beyond human comprehension, but also deep, most inward, as small as a mustard seed, secretly working, in such intimacy no less omnipotent and lovingly provident than in the galaxies and all the stars therein. For what is a star to God, but a grain of dust? But for the grain of dust called man, the Son of God took upon himself that humble state of being, and knew the loneliness of Gethsemane and the suffering of the Cross.

That should give us hope. When Gerontius passes from this world to the world beyond, he can be confident that Christ has traveled this road before him, and has prepared the way. The old man hears, as from afar off, the voices of people praying about his bedside, but nearby, right after our hymn, the prayers of the Angel who ministered to Jesus in his humanity, in the garden. “Hasten, Lord, their hour,” he says, “and bid them come to thee.” And thus is our hymn not at all sad, but triumphant, best sung to the rousing and cheerful melody NEWMAN — sometimes denominated as BILLING — by the organist, music historian, composer of sacred music, and collector of sea-shanties, Richard Runciman Terry. To sing this one at the top of your lungs in a great congregation of people who share the confidence and thankful joy — this is something we should all know.

Click on the image above to hear a beautiful choral and congregational rendition of today’s hymn.

Praise to the Holiest in the height, And in the depth be praise: In all His words most wonderful; Most sure in all His ways! O loving wisdom of our God! When all was sin and shame, A second Adam to the fight And to the rescue came. O wisest love! that flesh and blood Which did in Adam fail, Should strive afresh against the foe, Should strive and should prevail; And that a higher gift than grace Should flesh and blood refine, God's Presence and His very Self, And Essence all divine. O generous love! that He who smote In man for man the foe, The double agony in man 820For man should undergo; And in the garden secretly, And on the cross on high, Should teach His brethren and inspire To suffer and to die. Praise to the Holiest in the height, And in the depth be praise: In all his words most wonderful, Most sure in all his ways!

I came upon Newman's writings in my book Selected Sermons, at up to now, the most difficult part of my life. I fell in love. I will take up that book again. After reading your beautiful essay, I returned to my book and opened up to "...therefore day by day he unlearns the love of this world, and the desire of its praise; he can bear to belong to the nameless family of God, and to seem to the world strange in it, and out of place, for so he is." Thank you for rekinlding his fire for us.

I do want to be a pipsqueak in that congregation, singing with all my pipsqueak heart! Glory to God, and praise Him for all that sings....