Our Film of the Week comes from a director, Alfred Hitchcock, who I think has been, if anything, underrated because he was so good at one obvious thing, suspense, that people do not pay enough attention to where his heart and mind really lie. In his films, Hitchcock is always exploring what makes goodness so strong, even when it is misunderstood, and what makes evil self-contradictory and self-destructive. This he does without a trace of sentimentality, often by placing ordinary and decent people, or even people who are emphatically not saints but who are courageous and resourceful, in a sudden tangle of entrenched evil. These usually do not come from high society. They’re the midwestern doctor and his wife in The Man Who Knew Too Much, vacationing in Marrakesh when their boy is kidnapped by a British husband and wife working as international spies and assassins. Or it’s the thoroughly decent and unstoppable American reporter in Foreign Correspondent who learns, because he’s got his eyes wide open, that the famous leader of a peace movement in Europe is actually working on behalf of the German Nazis. And here?

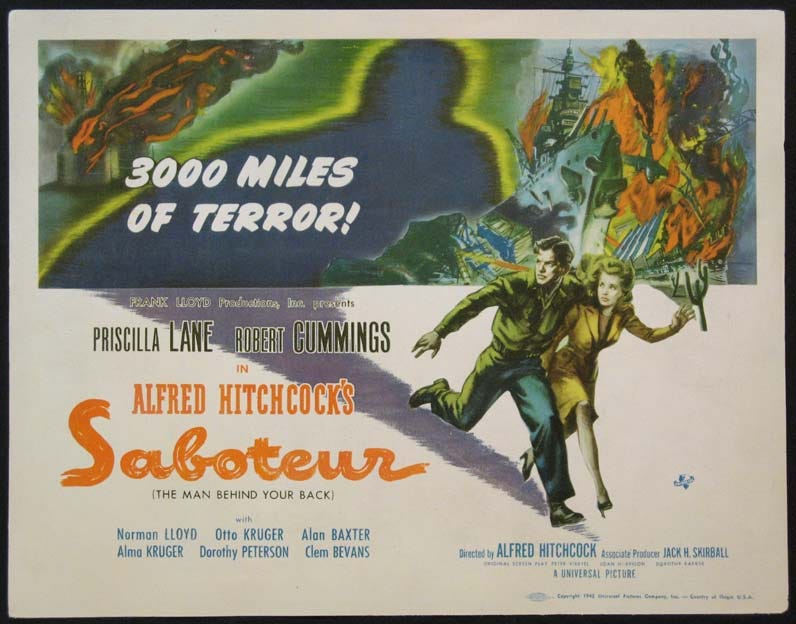

We begin at a wartime manufacturing plant in California, when a saboteur named Fry (Norman Lloyd in his first role) turns a fire he has set into a raging inferno by handing to an innocent employee, Barry Kane (Bob Cummings), a fire extinguisher full of gasoline. Kane hands the extinguisher to his friend who’s gone to help put the fire out, and when his friend sprays it, he engulfs himself in the flames and the whole place goes up in the conflagration. Of course, Fry doesn’t work there, nobody’s heard of him before, and the only reason Kane knows his name is that the man had accidentally dropped some letters addressed to him when he was in line with the other workers. He disappears, leaving Kane as the only candidate for being the culprit — and when Kane escapes from the police, it’s a double manhunt we’ve got. The police are after Kane, and Kane is after Fry, going first to the country estate he saw addressed on the letter. Sure enough, that estate is bristling with traitors and saboteurs, all passing as high-class people nobody would ever suspect as crime. They mean no good to Kane, either, and he will have to escape from them also. The manhunts will cross the nation, all the way to the Statue of Liberty, and one of the most famous final scenes in all of film history.

Hitchcock had originally wanted big-name stars Gary Cooper for Kane and Barbara Stanwyck for Pat Martin, a girl whom Kane meets soon after he escapes from the police, with handcuffs still on him; she thinks he’s guilty, but will come to learn otherwise. But Cooper wasn’t interested in the project, and Stanwyck wasn’t free, nor was Joel McCrea, the star of Foreign Correspondent. So Hitch turned, wisely I think, to the boyish and fresh-faced Bob Cummings, whom he would cast later on as the hero in Dial M for Murder, and Priscilla Lane, the ingenue in Arsenic and Old Lace. Their work together is perfect, just because they don’t appear to be acting — they simply seem to be what they are, readable by anybody. That’s all to their benefit in fact, because any trace of slyness or malignity or of jaded worldliness would expose them at once to everybody. One of the most powerful scenes comes when Pat’s Uncle Philip, a blind man, welcomes Kane into his out-of-the-way house and deliberately misleads the police, because though he can’t see with his eyes, he can see with his mind, and he trusts the boy.

Innocence is attractive, and so, in Hitchcock’s world, is loyalty and love of country. Hitchcock was an Englishman who loved America. There were such. We in America would look on Englishmen as our elder brothers in culture, and I sense that Englishmen looked on Americans as their younger country cousins across the water, cheerful, confident, sometimes clumsy, but without guile. I love Graham Greene as a novelist and a writer of screenplays, but he never gives an American a break. Hitchcock, though, shows us in Saboteur what treachery in one of its guises looks like: worldly-wise, strangely superficial, jaded, decadent, breathing the smell of corruption despite their tuxedos and fancy jewels and cement swimming pools and mindless factotums, and not really loyal to anyone or to any place. Pay close attention to the contrast between the blind uncle and his playing on the piano, in quite a humble and small home, and the foulest villain of the film, Tobin (Otto Kruger), rich, eloquent, “respectable,” high-toned, and empty in the soul. Hitchcock’s heart was with the people whom others would overlook. Some people I know say that he got that from the gospels — for Hitch was a believer, and it shows.

Many thanks for following along on our mission to restore every day a little bit of the good, the beautiful, and the true.

Andrew Klavan has a new book out, Kingdom of Cain, in which he writes quite a bit about the moral heart of Hitchcock’s work. I agree with you, he remains very underrated!

There are some that admire the movies he did in England, in black and white, and the people all talking funny. Some dame on a train, stuff like that.