Our Word of the Week here, or rather our entry for Figuratively Speaking, is the phrase “sea change,” which we use to describe not just, let’s say, a change from a pleasant village with a general store, a bandstand in the park, and a small brick school swarming with the neighborhood children, to a pleasant town with the same, but also a bowling alley and a movie house, but from that same village to a metropolis with office buildings and restaurants nobody can walk to and a consolidated district high school in what used to be a corn field. Or maybe the change goes in the other direction. Where I lived, my town and all the towns nearby were pocked with enormous hills of coal-flakes, hundreds of feet high, sheer waste, but we leveled them or dug them out, covered them with topsoil, and one of them now sports a park with a big ballfield, green and open to the sky, with a fine commanding view of the valley below and the mountains opposite, where people cheer their teams and get a coke or a hot dog from the concession stand. We were nowhere near the sea, but maybe that too would qualify as a sea change, so different is the terrain from what it used to be.

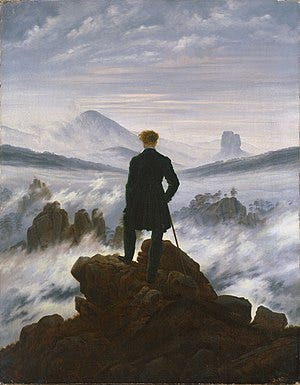

The first change I’ve described, from the homely village to the metropolis, should seem unsettling to any person of normal sensibilities, somewhat sad, perhaps even threatening. I’m recalling my last visit to 34th Street in New York City, to visit old Saint Michael’s church and rectory, which appeared like a last foothold of beauty and sanity and human feelings amidst new gigantic glass towers that say to man, “Come here and find your place, industrious ant that you are, or else go away and be poor.” But more often we use the phrase sea change to describe something wondrous, hope-filled, expansive. Where did it come from?

Shakespeare coined it. That shouldn’t surprise anybody! I think that around 40 phrases or sayings have entered common parlance just from Hamlet alone, phrases like “piece of work” and “to the manner born” and “alas, poor Yorick,” and sayings like “Something is rotten in the state of Denmark” and “Neither a borrower nor a lender be” and “The lady doth protest too much, methinks.” The Bard coined a lot of words, too, though sometimes it’s hard to be certain that he was in fact the first to use this one or that one. I once heard that he had coined the word important, but that turns out not to be so. Anyway, Shakespeare was not engaging in a flight of metaphorical fancy when he coined the phrase “sea change.” He really was referring to a change wrought by the sea, because it takes something vast and powerful, like the sea, to work the change he gives us in the play where it occurs, The Tempest. Brooks and creeks don’t have the power to do it. Human stratagems don’t. Pleasant wishes don’t. Even kings and princes don’t.

What exactly that sea change was, with the song in which the phrase occurs, I’ll save for Wednesday, with our Poem of the Week. But now I’d like to talk a little about that word, sea. It’s a great word: simple, yet unbounded by any consonant at the end. Its sound seems to suggest the boundlessness of the sea — unlike lake or pond. Now here’s a feature of languages that can both frustrate the linguist and set him searching for treasures no man has found before. I’ve often given you ancient Indo-European roots for our Word of the Week, because they often shed light on meanings that lie glimmering still in the word’s sense and use, and they can bring us into the company of cousins in the other Indo-European languages. But when our restless linguistic ancestors migrated from the steppes of Russia south to Persia and India, south and west to Greece and the other Mediterranean lands, and north and west to Europe all the way to Ireland and Iceland, they were swarming upon lands where people already lived and had their own languages, almost all of which were eventually lost, some of them without a trace.

So in Italy, a lot of place-names aren’t Latin in origin but Etruscan, which was not in the Indo-European family. Anyway, when that happens, you’ll get words in a language or closely related languages that have no relations in the rest of the family. Those words come from the unknown languages that were already spoken in those places. So it seems with the word sea. It’s in the Germanic languages, but nowhere else: English sea, German See, Icelandic sjo, and so on. The big family root for sea was mori-, which gives us Latin mare, Irish muir, Russian morye, English mere (now meaning lake, as in the place name Eagles Mere, a sparkling mountaintop lake about fifty miles from where I grew up). I guess the phrase mere-change wouldn’t work, because of confusion with the unrelated adjective mere, from the Latin merus, meaning unmixed, used of wine not diluted with water (see English neat for a similar sense).

And hey, a lot of names we think of as Latin aren’t really, including my own, Anthony, from Latin Antonius (the h isn’t original and doesn’t belong). It was an old family name in ancient Rome, but it probably came from Etruscan. What it meant, nobody knows.

Word & Song by Anthony Esolen is an online magazine devoted to reclaiming the good, the beautiful, and the true. We publish six essays each week, on words, classic hymns, poems, films, and popular songs, as well a weekly podcast for paid subscribers, alternately Poetry Aloud or Anthony Esolen Speaks. Paid subscribers also receive audio-enhanced posts and on-demand access to our full archive, and may add their comments to our posts and discussions. To support this project, please join us as a free or paid subscriber. We value all of our subscribers, and we thank you for reading Word and Song!

Listen to this episode with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Word & Song by Anthony Esolen to listen to this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.