At Sometimes a Song I often find myself writing about prodigies. Have you noticed? And our song today, written in 1888 for the United States Marine Corps Band, is the work of a musical prodigy, John Philip Sousa. Sousa has something else in common with many of the musicians who gave us the great flourishing of American music in the 20th century: he was a child of recent immigrants, his father from Spain and his mother from Bavaria. Sousa was the eldest boy and third of ten children in his family. Music was already in the air in his family by the time John was born. His father was a trombonist with the U. S. Marine Corps Band when he met Maria Trinkhaus in Brooklyn, New York, when Sousa, Sr., was touring with the band. Not surprisingly, the Sousas lived in Washington, D. C., within an easy walk of the Marine Corps Barracks. At the time of John’s birth, I am sure his family could hardly imagine what an honored place their son would hold in the history of their adopted country and in the hearts of their fellow Americans.

In the days before recorded music, and for long after the entrance of that technology on the scene, some musical proficiency was not uncommon among the common folk. And yet, John Philip had the uncommon advantage of being born into rare circumstances. He literally grew up in the company of The Marine Band and its music, and his father, likewise a musician, made very certain that his son had as solid a musical education as was open to him. As a child, young John Philip studied violin, piano, flute and several band instruments, as well as voice and music theory. He became so skilled on the violin that by the time he was thirteen (in 1868), his father feared that young John would be spirited away from the family by a traveling theatrical troupe. What’s a father of a prodigy to do?

Well, in those days one could ENLIST a minor son (at the rank of “boy”) in an apprenticeship with the Marine Corps in what we would now consider a work-study situation. And that is exactly what Mr. Sousa did. John Philip was actually enlisted in the Corps, an enlistment that was binding until he reached the age of majority, 21. It was this astute move on the part of his father that put John Philip Sousa in the exact position to advance his musical career while working essentially as an adult musician and with constant experience as a band performer, and later as a conductor. During these years, John also had theatrical performing experience on his own, and was popular at Washington venues, including Ford’s Theater, where (when John Sousa was only a child of 11 years), the president of the United States, Abraham Lincoln, was assassinated.

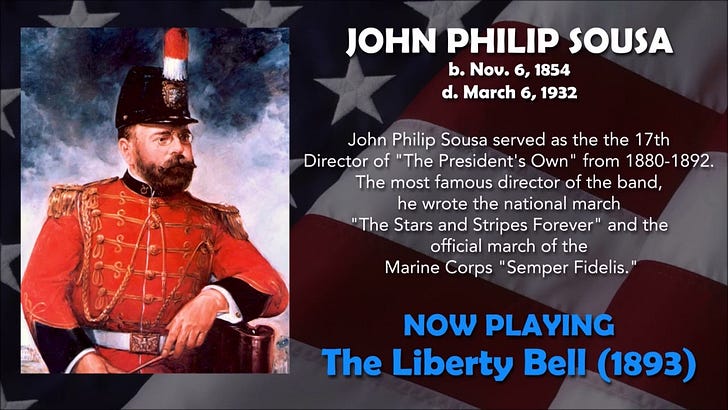

Who could know then that John Philip Sousa would grow up to lead The President’s Own Marine Band during the administrations of five U. S. Presidents: Rutherford B. Hayes, James A. Garfield, Chester A. Arthur, Grover Cleveland, and Benjamin Harrison. During his tenure as director of “The President’s Own,” John Philip Sousa turned the Marine Corps Band into a national sensation, with a world-wide reputation, not just for their musical skill (which was excellent) but for the artistry of their music, much of it penned by their director himself.

John Philip Sousa was not just a great musician, composer, conductor, and showman. He was also a great patriot. When he took The Marine Corps Band to England (before World War I), he earned international regard, and was dubbed The March King — quite a compliment, since formerly the title “King” had been used only for “The Waltz King,” Johann Strauss. For a composer, this designation was high praise, indeed. In WWI, Sousa was called out of retirement for a wartime commission as Lieutenant Commander, to resume the duties as director of The Marine Corps Band. Under his direction, that band set down some 400 recordings, despite Sousa’s disdain for the quality of the cylinders. (When flat shellac records were introduced, Sousa “changed his tune” and embraced the medium, but he did say — and he was right! — that the availability of recorded music would certainly make it less necessary and thus less likely that people would learn to play musical instruments themselves.)

After the war, Sousa returned to private life, but in the early 1920’s, he was given a permanent commission as Lieutenant Commander in the Naval Reserves, although he did not serve in active duty. John Philip Sousa was (and still is) so beloved that every year on his birthday, November 6th, The Marine Corps Band performs “Semper Fidelis” at his grave in the congressional cemetery. God rest his soul. Semper fidelis, indeed.

I hope you will enjoy the performances below of a few of the 145 marches that John Philip Sousa wrote over his long career.

Thank you for joining us at Word & Song!

I’ve always enjoyed Sousa marches, too! The Washington Post March is a favorite—and the idea of a newspaper having a march strikes me as hilarious. It never would have occurred to me. I have a soft spot for the Marines, too, as my son is an officer. He’s just back from Okinawa after too long an absence.

I admire the USMC! And I really appreciate the upbeat "marching" music today! Thank you.