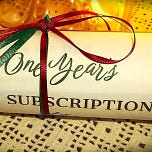

Advent is here, and so are our Christmas offers at Word & Song!

Now through Epiphany new paid, gift, and upgraded subscriptions are 25% off.

Paid subscribers see a special gift offer at the very bottom of this page.

Our readers at Word and Song will likely know by now how much I admire George Herbert, the author again of our Poem of the Week, and the man who is, to my mind, for perfection of form and precision of thought, unsurpassed among lyric poets in English. That’s high praise, I know, but I mean every word of it. Reading a poem by Herbert is like looking at one of Bach’s choral settings for a hymn. You say to yourself, “The only person who should dare touch this is Bach himself,” which in fact he did, giving us wonderful variations and arrangements of such melodies as Von Himmel hoch or O Jesulein suess, to name two melodies fit for this season. I should add that it’s by no means a mere flight of fancy to associate Herbert with Bach, because Herbert did some musical composition too, for the benefit of his parishioners, setting some of his own works to melodies. Indeed, Ralph Vaughan Williams, who did more than any man in the twentieth century to revive or to preserve folk melodies and carols from every part of England, saw that Herbert was eminently suited for music, and so he composed his Five Mystical Songs for four of the poet’s works (one of the poems is, in both Herbert and Williams, divided into two quite distinct parts). One of those four poems — or five songs — is in fact “The Call,” the poem I’m featuring today.

“The Call” is a deceptively simple poem: simple as a cut diamond is. There are three stanzas of four lines each. The first line is always the “calling” line, beginning with the imperative call, the word, “Come,” followed by three phrases, always the possessive “my” and a distinct noun of one syllable. The next three lines then take up, one by one, each of the three nouns, naming something striking, surprising, paradoxical about it. These lines all begin with the word “such,” as if to suggest to us that we may have encountered a way or a feast or a love before in our lives, but never such: these are unique, and only to be found in the divine Person who really is always the object of the verb “Come,” namely Christ. So if we think of the stanzas as explaining the terms of the Call, we’ve got three stanzas of three lines with three names, and in the final stanza, it’s really three in a kind of trinity, since the final name, the Heart, is described in terms of the other two names.

Of course, we usually think of the Call as coming from God to us: we are supposed to hear Him when He calls. But every prayer is a call to God — as Herbert says in the poem “Prayer,” it is like “reversed thunder,” an “engine against the Almighty,” meaning a siege engine, like a battering ram. So in this poem, Herbert calls on God, and in doing so he calls Christ by nine terms, three by three. That’s not just to describe Christ. It’s to make a confession. To say, “You are my joy,” is to say something about both persons, the one who speaks and the one who is addressed. And more, when you think about it. It’s to say something about the bond between the two, the yearning of the soul for God, and this yearning is itself inspired by God; it’s God Himself acting in the soul.

I’ve said that each of the “such” lines says something about Christ that is paradoxical or surprising — actually, unique. Look at the line, “Such a feast as mends in length.” The Christmas feasts I remember from my childhood were wonderful. When I was a bit older, we had a pool table in the basement, and my father, my uncles, and I and maybe one of the other boys would play a kind of game for dimes and quarters, an exciting game with surprises, because you’d get a quarter from everybody else if you knocked your ball in, but nobody knew which one that was, and you couldn’t just shoot at the ball directly, since the only shots that counted were those in which the cue ball struck first the lowest-numbered ball on the table. Anyhow, I loved that game, and I was pretty good at it, and I could have played it for two solid hours, but I don’t know if even I could have held out for three. Eventually, everybody gets tired, and you start glancing at the clock. Any human gathering will be like that: it has its rise and its peak, and then its dwindling away, till it is time to go home. The wedding at Cana would have broken up right away if Jesus had not worked his first miracle, but even then, the new wine did not hold up forever. Only this feast grows more joyful the longer it goes on: it “mends in length.” “Further up and further in!” cry the happy adventurers at the end of Lewis’s novels of Narnia. It is the story whose final page is the first, and always new. Love never ends, says Saint Paul.

Come, my Way, my Truth, my Life: Such a Way, as gives us breath: Such a Truth, as ends all strife: Such a Life, as killeth death. Come, my Light, my Feast, my Strength: Such a Light, as shows a Feast: Such a Feast, as mends in length: Such a Strength, as makes his guest. Come, my Joy, my Love, my Heart: Such a Joy, as none can move: Such a Love, as none can part: Such a Heart, as joys in love.

Listen to this episode with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Word & Song by Anthony Esolen to listen to this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.