Join us for Poetry Aloud (Friday podcasts) this summer, when Dr. Esolen will continue to read Huckleberry Finn, chapter by chapter, in its entirety.

Today, while I was out walking Molly the Puppy Terrier, I came to the Japanese plum tree that stands on the front lawn of a local old folks’ home. I could tell that the fruit was ripe, or nearly so, because quite a few of the little globes were lying on the grass, having turned pinkish-purple — it’s really a handsome plum, the Japanese, and often you’ll see a shading of color from saffron yellow to pink to purple almost to violet, on a single fruit. They’re a little bigger than ping-pong balls, very sweet and juicy, with a sort of flowery flavor, much better than the gritty purple plums you get in the store, with their pits cracking and sometimes sticking a shard between your teeth. So I ate a few, and I thought, “Maybe I should come back here with a bag and gather up the ripe ones, since nobody else will bother.” I could at least get the windfall — literally, the fruit the wind brings to the ground. You see, a lot of fruit trees can be quite tall, and then you have to wait for the wind to knock the fruit off the branches, and you hope they don’t get bruised too badly when they hit the ground.

Our Word of the Week, you’ll remember, is fruit, and one of its relations is the word frugal, which describes somebody who makes good and careful use of the fruits of his labor, or, for people who live off the land, the fruits of the earth. Frugality is a virtue, to be sure. And the author of our Poem of the Week, Robert Frost, was a frugal man. You have to be, if you are going to try to farm this flinty New Hampshire soil where we live. It sure isn’t Iowa, with black topsoil that looks good enough to eat, two feet deep! Yet Frost also knew that frugality isn’t the most important of the virtues. There’s something more important than knowing how to use everything that comes your way. It’s knowing how not to use it, but to enjoy it as it is, or to leave it alone. Italian frugare thus means to search, to rummage around, to try to get out of something everything you can; it suggests restlessness, even to exhaustion. Imagine somebody who goes all around town gathering up every single fallen fruit he can find. What’s wrong with that? Well, it won’t just let things be.

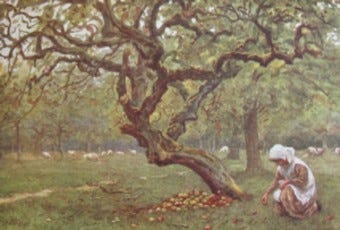

So then, the speaker in Frost’s poem — we’ll just assume that it’s the poet himself, for the sake of simplicity — comes upon such a summer windfall. He doesn’t at first see it. He smells it. To this day, if I suddenly catch the scent of fallen apples, I seem to be a boy again, on our street where a couple of tall apple trees growing wild dropped their bruised apples on the road below, and of course, being boys, we’d hit them with a baseball bat or try to nail a street-sign with them from twenty or thirty yards away. Sometimes, if an apple looked good enough, we might pick it up and eat it, first checking for worm-holes; sometimes they were sweet, but when they were sour, you had the chance to spit the pulp out at something, and that also was fun. But it’s the principle that Frost is after here.

Often, Frost will leave the principle for us to guess at, if there is a clear principle at all, as in the poem "Mending Wall" — something, he says, and never tells us what it is, “there is that doesn’t love a wall, / That wants it down.” But here he tells us outright, or at least he makes a strong suggestion. It is good for us not to harvest everything. Why? There’s the thing. “So smelling their sweetness would not be theft,” he says. But what does he mean by that? What kind of world would it be, where you never had any fallen apples to smell?

One more note on the poem. Frost writes it in rhyming lines of accentual tetrameter, one of the common meters for English folk songs and ballads. What I mean is that each line has four strong beats, which you may think of, musically, as quarter notes. Before each of these strong beats, you get either one or two weak beats. If it’s two, you can think of each as an eighth-note, taking up half the time as you’d take to pronounce one beat. The effect is to speed up the line, that is, to make us speed up when the line contains those “extra” syllables, so that one line will take the same time as another. It’s a meter that can easily suggest light-heartedness, as it does here.

A scent of ripeness from over a wall. And come to leave the routine road And look for what had made me stall, There sure enough was an apple tree That had eased itself of its summer load, And of all but its trivial foliage free, Now breathed as light as a lady's fan. For there there had been an apple fall As complete as apple had given man. The ground was one circle of solid red. May something go always unharvested! May much stay out of our stated plan, Apples or something forgotten and left, So smelling their sweetness would be no theft.

Listen to this episode with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Word & Song by Anthony Esolen to listen to this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.