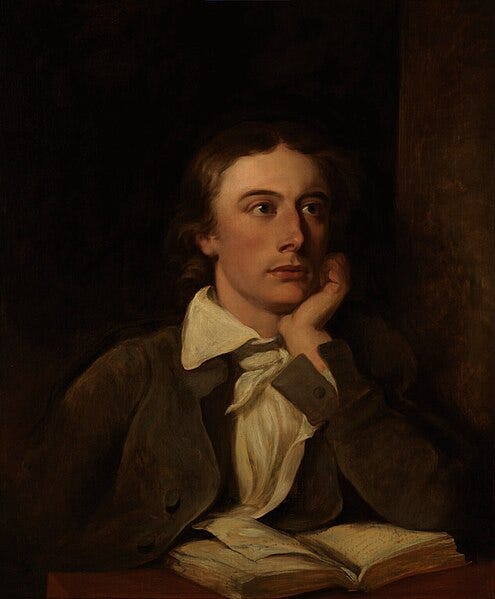

Our Word of the Week, romance, might lead you to think that we’d feature a love poem today, and in a way, that’s what we have here, though it’s kind of an indirect way. John Keats, our poet, did not grow up with wealth, and he did not have the high education that his fellow Romantic poets had. That’s why he had to rely on a translation of Homer by the Renaissance poet George Chapman, a vigorous and rough-edged work indeed, and Keats was so enthralled by it, he gave us the best sonnet in English on finding another world when you read a book that takes you far away in time and place and culture. I’ve read some criticism of Keats’ work at the time, when he was lumped in with a few others as “Cockney” poets, so that every time the young man tried his hand at entering the world of classical Greece, or even the nearer worlds of medieval and Renaissance Europe, the critic treated him as you’d treat a hillbilly from Tennessee trying to speak Parisian French and to order “vishy swazz” at a cafe.

The thing was, though, that Keats was a prodigiously intelligent man, possessed of a keen sensibility, and immense creative vigor. To put the classics in front of him was like setting a young Einstein in front of the universe. I’d say of him what I’d not say of anybody else in English history, that if he had lived longer, he might have stood alongside Shakespeare. I say it because his work was changing and growing more sophisticated and complex, at breathtaking speed. He had in great measure what he himself called “negative capability,” and he didn’t mean anything negative about it. It’s the capacity to withdraw yourself and, in imagination, to feel what it is like to be someone else, or to let a work of creation or a work of art enter your soul, without first twisting its arm so that it will say what you want it to say. It’s the reverse of politically motivated art — not that Keats didn’t have, personally, strong political feelings.

And there’s something else that may account for Keats’ sense of urgency. He had consumption — tuberculosis. He probably caught it from his elder brother Tom, whom he nursed while the man was dying; Keats had studied to become a physician. He died at age 25, but he’d already stopped writing poetry for some time, out of sheer weakness. But here’s the heart of the romance in today’s poem. John Keats had met a young woman, Fanny Brawne, and the two had fallen deeply in love. Their courtship lasted for three years; Keats wanted very much to marry her, but he would not do so until he was settled in work that could support a family. He had no fortune of his own. The two wrote to one another all the time; and after Keats died in Rome in 1821, Fanny went into mourning for six years, though afterwards she did marry and raise a family of her own.

What we have in this sonnet, then, one of the last of Keats’ poems, is a reflection on the shortness of his life, and his two-fold fear: first, that so much of the poetry that seems to be coming alive in his mind will never reach fruition, will never be gleaned as “full ripened grain,” and he will never read the stars above as the “cloudy symbols of a high romance”; second, and more important, that he will never look on Fanny again, and never be moved by the magical “power / Of unreflecting love.” For Keats, there is no answer to this fear. What he believed about God and immortality was still in flux. All he can say is that he has nothing to say, and the final line of the poem, quietly and effectively, simply ends, not with a climax, but with the fading away of the poet’s voice. Well may we read the inscription on his headstone in the Protestant cemetery in Rome, where I have stood three times: “Here lies one whose name was writ in water.”

When I have fears that I may cease to be Before my pen has gleaned my teeming brain, Before high-pilèd books, in charactery, Hold like rich garners the full ripened grain; When I behold, upon the night’s starred face, Huge cloudy symbols of a high romance, And think that I may never live to trace Their shadows with the magic hand of chance; And when I feel, fair creature of an hour, That I shall never look upon thee more, Never have relish in the faery power Of unreflecting love—then on the shore Of the wide world I stand alone, and think Till love and fame to nothingness do sink.

Listen to this episode with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Word & Song by Anthony Esolen to listen to this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.