One of our most beloved hymns of remembrance, included in many an Episcopalian hymnal, originally had the title, Yesu bin Mariamu, as it was written in Swahili by the Anglican missionary, Edward Stuart Palmer. Once I saw that title, the linguist in me said, “No, it can’t be — bin Mariamu sounds Semitic!” Well, so it is. That’s because the Muslim Arabs did a lot of trading and conquering along the east coast of Africa, so that about fifteen percent of the words in Swahili are Arabic in origin, including the common word for son, here bin — as in Hebrew ben, so that Ben-Hur means Son of Hur, and ben-Adam means Son of Man, and so forth. Anyway, Palmer composed our Hymn of the Week in Swahili, when he was working in Zanzibar, some time before he left there in 1901 for reasons of health. By the way, the name “Zanzibar” itself isn’t Swahili or Arabic, but Persian (!), and apparently its origin in Persian may come all the way from China. People do get around. And Palmer wanted his poem to get around, too. In Swahili, he used lines of six syllables each, which he then translated into an English poem, in 6-5-6-5 meter, that is, six syllables and five syllables, alternating, so that if you use a melody for the one, you can easily adapt the same melody for the other. I guess I can’t complain about the translation, even if I could read Swahili, when the author and the translator are one and the same person!

The poem is deeply touching, so much so that I dearly wish I could find some others that Palmer wrote, as I guess that if he could do this well with one poem, and in two very different languages, he surely could have written more. The first stanza — or the first two, if you divide them into four lines each instead of eight — is pure love and adoration. Only afterward do we get to the petitions. But I think we can consider that first line, “Jesus, Son of Mary,” as doing more than getting a name out there for consideration. Let’s think about it. The typical thing would have been to call him the Son of Joseph, except that Joseph was his foster-father; so to call him “Son of Mary” implies that he is the Son of God. Then why not say “Son of God”? I think it’s because “Son of Mary” places him in that most tender of human relationships, that of mother and child. “Woman, behold your son,” said Jesus from the Cross, giving the beloved disciple John into her supremely maternal care, and “Behold your mother,” giving to John the responsibility to provide for her and to protect her, and, of course, implicitly encouraging him to heed her, and to honor her.

From this relationship, it is wholly natural for Palmer to turn to all other human relationships, especially those between the living and the dead. Most of the time, of course, it is the child who in piety will remember his father and his mother who have gone before him. But it could be anyone: a brother or sister, a friend, a teacher, a neighbor, even a child. And when we think of the specific person, as I believe the poem encourages us to do, we think of the actual wounds they suffered in this warfare of life. We think with pity upon them. All I need to do is to call up the face of my grandfather, and I see that man, shy, stubborn, extremely smart, speaking English with a heavy Italian accent, who after sixteen years in the coal mines had a nervous breakdown and could never hold down a job again. He was not lazy; he farmed his small plot of land so that the family always had vegetables, some fruit, eggs, and the occasional chicken; but it was all we could do to get him out of the near vicinity of his house. I loved him dearly, with all his flaws, and they were many, and with his virtues, which he did impart to his six children, most markedly to the three boys, who would do anything for him and my grandmother, without hesitation and without complaint.

Those three boys are now gone, too, my uncles, each of them also a little bit shy in his own way, each one with his flaws, in one case quite considerable, and yet each also bruised this way or that in the strife of this world, and each somehow ultimately within the fold. I don’t believe I ever said to a single one of them that I loved him. That wasn’t done. But I did and I still do, more than I have the words to express, since a lot of it is hard for me to explain. It’s that when I think of them, I don’t see the faults, but rather I remember them at our house shooting pool for dimes and quarters, with my father and me and a couple of the other boys; or I remember my Uncle Tommy taking a break from his work to be the “official quarterback” for us in a touch football game; or my Uncle Joe showing me his coin collection, which was considerable; or my Uncle Frank, my sponsor at Confirmation. They needed healing, and so do I — a lot more than it’s comfortable to consider. So we pray, in this hymn, to the Good Physician, for that final and ultimate healing. Ask, and it shall be given.

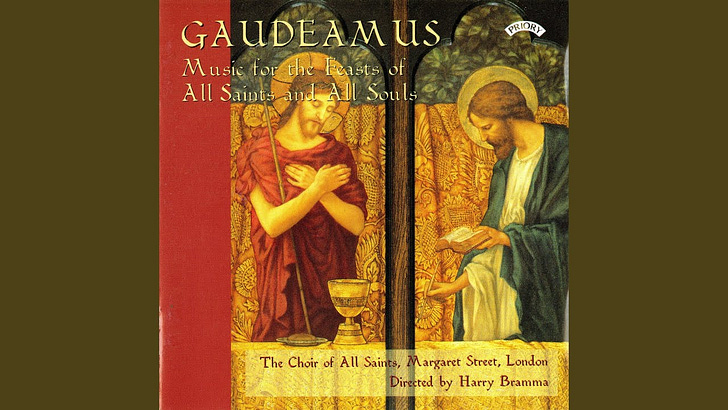

The tune for our hymn as sung by The Choir of All Saints (London) is an arrangement of a composition by Johann A. P. Schultz (1785).

We are including below an organ version of Adoro Te, the chant tune many of our readers may be accustomed to hearing with “Jesus, Son of Mary.”

1 Jesu, Son of Mary, fount of life alone, here we hail thee present on thine altar-throne: humbly we adore thee, Lord of endless might, in the mystic symbols veiled from earthly sight. 2 Think, O Lord, in mercy on the souls of those who, in faith gone from us, now in death repose. Here 'mid stress and conflict toils can never cease; there, the warfare ended, bid them rest in peace. 3 Often were they wounded in the deadly strife; heal them, Good Physician, with the balm of life. Every taint of evil, frailty and decay, good and gracious Savior, cleanse and purge away. 4 Rest eternal grant them, after weary fight; shed on them the radiance of thy heavenly light. Lead them onward, upward, to the holy place, where thy saints made perfect gaze upon thy face.

You have retrieved and illumined another gem.

How the hymn brightened my achy day. I will treasure it. Loved the commentary. Ha! You sowed the seed of that mining metaphor. Truth be told even Pennsylvania mined coal had its use, and I remember the scent of it.

Thanks for this hymn & our word of the week, and Happy November, Remembrance Day, All Saints and All Souls to you and the readers. May we remember and honor our fathers and mothers, and uncles…and all they dared and dreamed. As believers we long with Newman for the night to end and for Jesus to bring that bright Morn in which “those angel faces smile/which I have loved long since/and lost a while.”