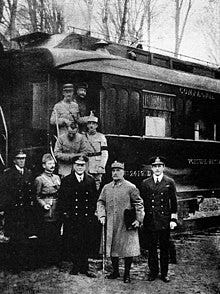

The day was November 11, 1918, and Marshal Ferdinand Foch, chief of the Allied Forces, was in his private railway carriage near Compiegne, about eighty miles north of Paris. He was waiting for the eleventh hour of the day, to sign the armistice that would end World War I, or rather, as he himself said, that would provide a twenty year truce. But Foch understood the meaning of the date. November 11 was and is the feast day of Saint Martin of Tours, and that brings us to our Word of the Week, remembrance.

Martin was born in 316, to a father who was a military tribune, so that by law the boy was enrolled in the Roman army when he was still quite young. His very name, Martinus, means Little Mars, that is, Mars the Roman god of war, for which that bright red neighbor of ours in the sky is named. But he was attracted to the Christian faith, nor was that an odd thing among the camp soldiers at that time, for the Emperor Constantine had made Christianity legal in 313, and he clearly favored it himself, though he was not baptized until he lay dying. Now, the famous story has it that Martin was riding along near the gates of Amiens, where his regiment was stationed, when he met a beggar coming toward him. The beggar was clad in rags and shivering with cold. So Martin promptly took his own warm coat, cut it in half, and gave one part to the beggar. That night he had a dream in which he saw Christ himself wearing the cloak, and telling his angels that Martin had given it to him. Martin left the army straightaway, was baptized, and in the course of years, after having studied under the great Saint Hilary of Poitiers, and having lived as a hermit and a preacher in the backcountry, he ended up, against his will, being raised to the bishopric of Tours, on July 4, 372. Martin had a long life, deeply involved as a peacemaker in a variety of political, military, and ecclesiastical conflicts. Marshal Foch, the professional soldier whose faith was more important than anything else in his life, remembered these things, which is why he wanted Saint Martin’s Day — Martlemas, as it was called in England — to be the day when the warring sides would lay down their arms.

When I was a boy, we still called November 11 Armistice Day, literally the day when military arms stand still. Then it was changed to Veterans Day, to be celebrated on the second Monday of November, which I think is unfortunate, because the specific date and the terrible war that it put to an end are forgotten. In England, the day is called Remembrance Day, though I do not know to what extent people still associate it with World War I. But let’s think about this matter of remembrance. Our year-old terrier Molly remembers quite a lot: people, places, things to eat, cats to chase, and so on. She even dreams about them, as we can tell when her eyes are shut but her nose is working or her paws flurrying a little, or stifled barks come from her throat. But she does not possess remembrance. Animals can remember; they could hardly survive if they did not. But man memorializes; he considers his memory; he commits things to memory by free acts of his will; he honors by making remembrance. We can go farther. Human culture has no meaning at all without remembrance, and this is so regardless of whether the people are literate. Consider that the works of Homer, the prince of poets, were not written down until several centuries after he composed them, even though the Greeks in Homer’s time did have writing. Culture is the memory of man extended across the multitudes at any one time and across the generations from age to age. In this respect, forgetting is a kind of death, and consigning to oblivion is a kind of murder, whereby you kill the dead more dreadfully than death itself had done. But memory, or rather calling to remembrance, is an act of life.

You may ask, “Does the word remember have anything to do with the word member?” That is, when you remember, do you re-member, restoring a member to the body? Alas, no, they aren’t related. The latter word has to do with flesh, the former, with the mind: Latin memor, mindful; sometimes sadly so, as in Greek mermeros, care-ridden, pensive; Welsh marth, anxious. The giant Mimir was the advisor to the chief of the Norse gods, Odin; his name suggests wisdom. “All right, then,” you sigh, “how did that b get in there?” I’m glad you asked. Put your lips together as if you are going to make the sound m. Press them hard and then make a vowel sound, as if it comes out exploding. What sound did you almost make? Wasn’t it a b? For that too is made with the lips and the voice box vibrating. The same sort of thing happens with d after n and g or k after the sound we spell as ng. Other English words with an intrusive b after m (sometimes picked up before the word got into English, as in French or Spanish): chamber (Latin camera), number (Latin numerus), thimble (the b in thumb is not original; see German Daum), ramble (a “frequentative” of roam, suggesting that you’re roaming hither and thither). For intrusive d after n, see hound (Latin canis).

And may God bless and keep all those who in war laid down their lives that others might live free.

Listen to this episode with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Word & Song by Anthony Esolen to listen to this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.