It’s Memorial Day today in the United States, what used to be called Decoration Day, because that’s when everybody went to the graves of their kin to tend them and set down some flowers — at least, that’s what we did in Pennsylvania. Of course, the day was more specifically in honor of soldiers who had passed away, especially if they had died in battle. I’ve described before, I think, what the custom was in my town, Archbald. Early in the morning, my cousins Frankie and Bobby and I, and a couple of the neighbor boys too, would troop along with the parade — and there’s our Word of the Week — to the Protestant cemetery high on a hill on our side of town, where seven of the veterans in uniform would fire their rifles three times, the 21-gun salute, and then, as the smoke slowly cleared in wisps of burnt gunpowder, another of the veterans would play Taps. Otherwise everything was perfectly silent. We were in awe of that. And now that I think of it, awe is a great word for another week, from our native Anglo-Saxon stock.

But then came the parade in earnest. For two or three years running, we managed to hop a ride on one of the fire trucks as they went their slow way through town; that was a heck of a lot better than watching the parade. The firemen didn’t mind. As I remember, it took us about an hour and a half to go nearly the full route, on up to the Catholic cemetery on a hill on the facing side of town — our town was built on a narrow defile cut by the Lackawanna River. There the whole parade stopped as one of the priests said Mass. When Mass was ended, the parade completed its last leg, coming down from the cemetery to the American Legion building on Main Street, where the Legionnaires gave everybody free doughnuts and orange juice. I loved it.

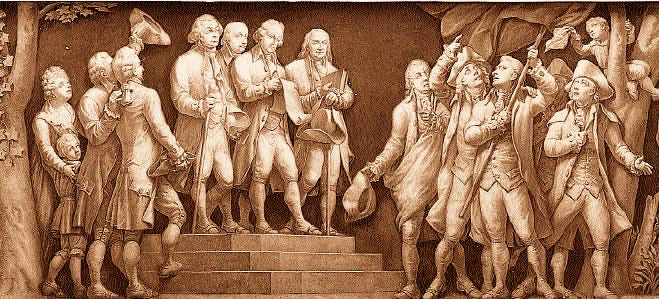

Parades, as far as I know, quickly became a thing of the past for the towns in our valley, but there’s one that I remember very fondly. It was the summer of 1976, Archbald’s centennial, and also the centennial of St. Thomas Aquinas parish. In those days, it was not much of an exaggeration to say that the town was the parish and the parish was the town. Anyway, people got the idea that it would be a good thing if everybody dressed up in old-style costumes, and if the men grew beards. That was the only time I ever saw my father with a couple of weeks of growth on him — he shaved it off when the celebration was done, but some of the men decided to keep theirs. So it was a parade in which there were almost as many participants as there were people watching from the sidewalks — actually, from the side of the road, since our town was mostly too poor for sidewalks, and I don’t think we yet had any street signs.

The celebration was notable for two other things. One was that a priest, a cousin to all the plentiful McAndrews in town, wrote a very handsome history of the parish, which was also a history of the town, complete with fine photographs. It couldn’t be written now, I think. It’s of high literary quality without the least bit of showing off, and of course there was nothing flippant, merely informal, topical, political, or off-hand about it. It was there only that I learned that the Italian who painted the murals and the ceiling of our church had done work on the Capitol rotunda in Washington, D. C. The other notable thing about the celebration is that it was the last time the town’s own high school was used for anything. The school was a very handsome building within a few hundred feet of the Catholic parochial school I attended, the Church, the rectory, the convent, and a small Knights of Columbus building that doubled as a candy store. After the celebration, the high school remained vacant, till finally they tore it down, made a little garden of the spot, and put up a plaque to commemorate what used to be there. Somehow, even though I did not attend either that school or the consolidated three-town’s monstrosity they built to replace it, I feel as if that spot and that plaque make up a cemetery of their own, a remembrance of a kind of town life that no longer exists.

A little bit on the word parade: it’s from Italian, through French and on into English. A lot of the words with -ade as a suffix are in the same category. Italian parata referred to a military drill, or something prepared in a big and fancy way, with a lot of fuss and feathers; that became French parade, entering English in the Middle Ages. The same sort of development gave us words like charade and stockade, and then, by analogy, applied to the hotheaded Rodomonte in Ariosto’s wonderful mock-epic Orlando Furioso, the word rodomontade. An Italian drink flavored with lemons is limonata, as you might say “lemoned”; it entered French as limonade, then English as lemonade. But then the English chopped off the suffix and stuck it onto other fruits, as in limeade and orangeade, and then they heard it as a word in its own right: ade. Imagine somebody speaking another language hearing an English suffix as its own separate word — say, “ing”. “Too many ings today!” says the busy shopkeeper. Better to pull up a chair and watch other busy people parading by.

Note: Our full archive of over 1,000 posts, videos, audios is available on demand to paid subscribers only. We know that not everyone has time every day for a read and a listen. So we have built the archive with you all in mind. Please do browse, and please do share posts that you like with others.

Thank you, as always, for supporting our effort to restore every day a little bit of the good, the beautiful, and the true.