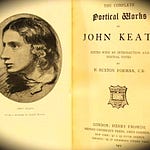

In 1926, the poet T. S. Eliot, a man of immense learning and relentless thought, entered the Anglican Church and became a Christian. “Oh dear,” said the novelist Virginia Woolf. “How can we invite him to our parties now?” For she and her husband, like all of the people in their fashionable set, were atheists. For Eliot to become a Christian, in her …

Listen to this episode with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Word & Song by Anthony Esolen to listen to this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.