I have a good ear for birdsong — I’m not sure why, though I suppose that such a skill would be handy for people hunting wild game, sort of like having a map in your mind of what trees and bushes and likely animals are all around you, with the songs giving you clues. Anyhow, I can tell when the orioles are back up north by a single note, the male’s loud whistle during the spring mating season, which he’ll sometimes give nine or ten times, taking a minute or two to do it, till finally he bursts out into his clear and melodious song. Orioles are among the most colorful birds you’ll see in a residential area in the eastern United States: orioles, blue jays, cardinals, swallows, and finches purple and gold. But our orioles are related to what we here call blackbirds, our Word of the Week.

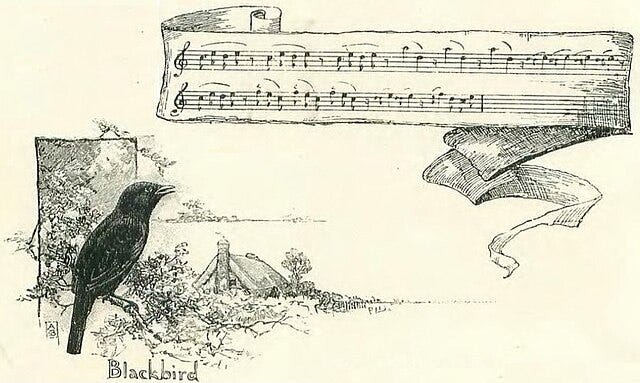

English speakers everywhere will remember the nursery rhyme that children have been taught to sing, with the “four and twenty blackbirds baked in a pie,” and when the pie was opened, “the birds began to sing.” The odd thing about that for Americans is that our blackbirds that are black — so that leaves out our wonderful orioles and the meadowlarks of the Midwest — don’t sing. They squeak and croak (the grackles), they have one not unpleasant call (the red-winged blackbirds), they gurgle a little, like ball-bearings grinding (the cowbirds), but they aren’t singers. That’s a lot different from the English blackbird, which is really a thrush, and as far as I can tell, all the thrushes are excellent melodists. My own favorite is the Wood Thrush, whose sudden trills are downright ethereal. But I do remember that my Italian cousins used to keep one of those European blackbirds in a cage — or maybe it was a Myna-bird, but whatever it was, its song was loud and bright and cheerful.

“So why did you pick the word blackbird for this week,” somebody may well ask me, “if your favorite American blackbird is mostly orange?” A good question! I like birds, first of all, and I’ve noticed that the bluebirds have returned to our neighborhood, which delights me; their main enemy has long been the House Sparrow, which like the Starling was introduced into the United States, or so I’ve heard, by some darned fool who wanted every kind of bird mentioned by Shakespeare to have some nests over here, too. Well, they have nests all right — in our cities and suburbs they are downright pests, and are to native birds what kudzu has been to our roadsides in the south. But there is something peculiar about the word blackbird that may be hard for people who don’t speak a Germanic language to pick up on. It’s the pitch of the syllables, the music of the word. The bluebird is a blue bird — notice the difference? Genetically, a blackbird may not actually be a black bird; our oriole is more orange than black, as I’ve said. By the time an English-speaking kid is three or four, he’ll know that the white house at the end of the street is not the same as the White House, and we don’t really say them the same way. Even though we spell White House as two words, we pronounce it as one: it’s the WHITE-house. In German, the convention is to spell even long compounds as one word: so the Feuerwehrhauptmann is the Fire Department chief; but there’s not a pfennig’s difference between how the German pronounces that single word and how the Englishman pronounces those three words as really one compound word: it’s the FIRE-department-chief.

How do we learn these things? Linguists like to sit back and listen, and think about words, and take note of what people do mostly unconsciously, countless things that are actually kind of hard to describe, involving pitch, stress, sounds that aren’t the same but are “heard” the same, little breaches in pronunciation, a breath here and a clutch in the throat there, an extra vowel that people don’t even know they’re pronouncing. That’s in English. Imagine what it’s like to speak Mandarin Chinese with the four tones, so that “ma” can mean “mother,” “hemp,” “horse,” and “scold,” depending on what music you make with the vowel. But gosh, what if you’re aggravated with your mom, and you say, “Ma!” — did you just call her a horse or a rope? But then, when I was teaching some Italian boys a little bit of baseball, and I called out, “Strike!”, not aspirating the final k, the boys couldn’t hear it at all — they thought I said, “Stri!” I suppose they’d find it tricky also to tell the difference between a bigwig and a big wig, a bluestocking and a blue stocking, a lighthouse and a light house. And as for me, when I was a kid I always heard it as Madison / SQUARE Garden, not as Madison Square / GARDEN. Heck, I thought it had to do with boxing rings, which unlike every other ring in the world, are square!