On the fifth day of creation, God commanded the waters to bring forth the fish and the creatures of the sea, and the birds of the air “to fly above the earth in the open firmament of heaven.” And that is when God gives his first blessing, “Be fruitful, and multiply, and fill the waters in the seas, and let fowl multiply in the earth.” Think of it: it is to the creatures that do what man cannot do, living where man cannot live, in the depths of the waters and in the skies above. Yet man has always looked to the birds for their loveliness, their song, and their inspiration: we want to mount, as on the wings of eagles.

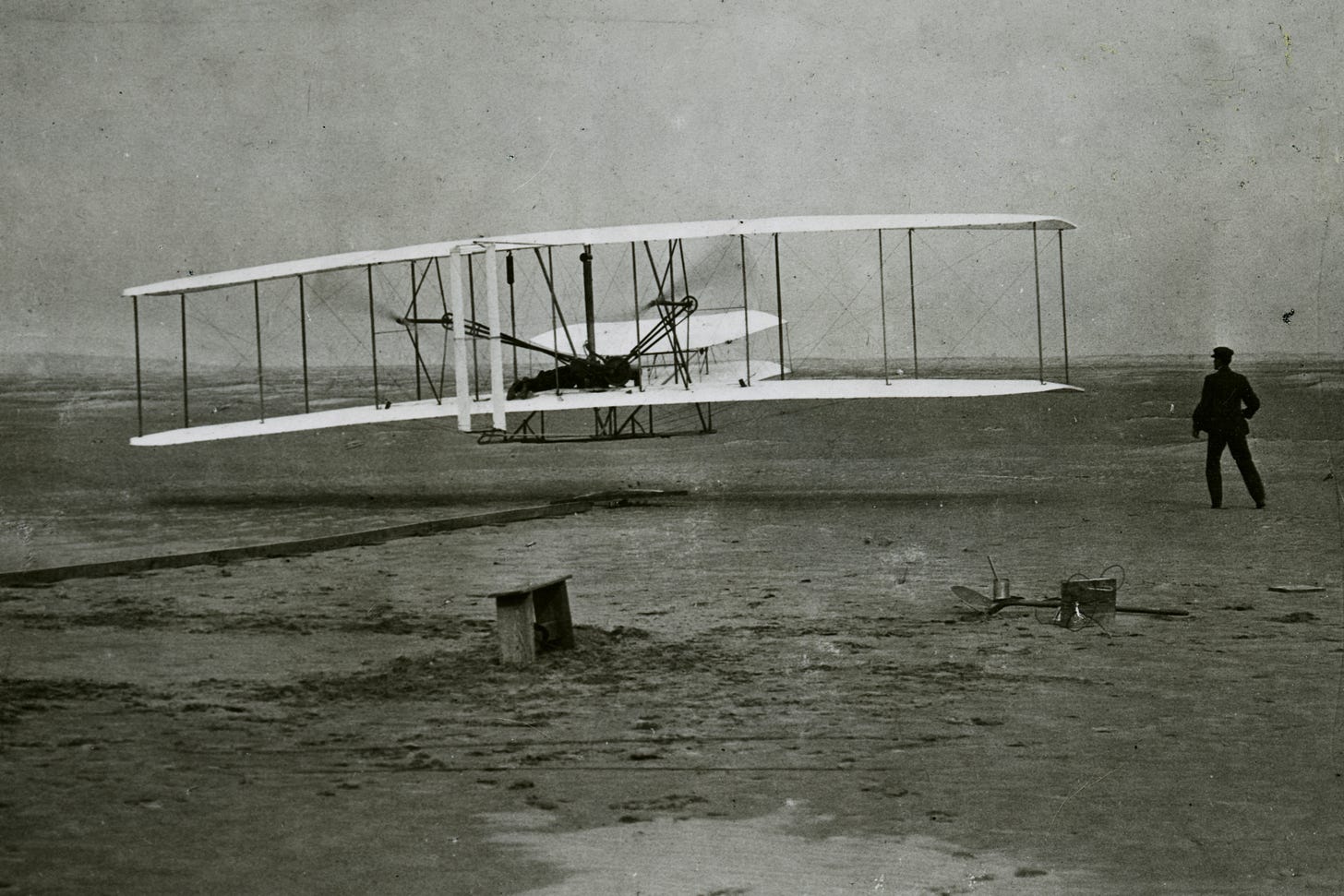

Samuel Johnson once wrote that the problem of flying was the same as the problem of swimming: the thing to do is to push the water or the air back behind you faster than the water or air in front of you can rush in to take its place. That’s what propellors do, I guess. Airplane wings, shaped rather like the wings of birds, force the air above you to get out of the way faster than the air below you, so that the air below bears you up. I hope I’ve got this right. I’m not named Orville or Wilbur, after all. Still, why does man want to fly, even if he has no particular place in mind to fly to? Dogs have no ambition for it. Maybe it has to do with the launching forth of man’s mind. Picture a little boy on a sunny hill, lying on his back and gazing into the open sky above. That is a picture of man: he looks, he wonders, he never says to his mind, “Thus far and no farther.” It’s not only ambition that spurs him on. The little boy has no ambition. It certainly isn’t pride, which weighs you down. It is wonder, and the delight in sheer play. “Angels can fly,” said Chesterton, “because they take themselves lightly.” Lucifer didn’t, and he fell.

And think of how we use the image of flying: always more in play than at work. We call it a flight of fancy when somebody does a thing in a rush of imaginative fun, as when, for a pet parade, we got up our terrier in a bonnet and a dress and put her on a little stagecoach, reading, “Go west, young Dog!” It didn’t move very fast, that stagecoach, but the idea for it, Debra’s idea, had wings. It’s been 700 years since we in English have used fly to describe going at full speed, and again I think that it had more to do with daring and dash and merriment than with, say, the terrified retreat of an army. So Chaucer’s Squire tells a romantic story involving a flying horse, like Pegasus of old — which he doesn’t get to finish, because while his imagination soars, his skill in constructing a plot still plods along the ground. Ariosto’s happy knight Astolfo gets hold of a flying horse and learns how to ride him, so he can whisk about the world and see all kinds of things and meet all kinds of people, including, on a very high mountaintop in Ethiopia, the evangelist Saint John, who has his own horse-drawn chariot for riding in the air, even as far as the moon, where Astolfo’s got to go because — well, you have to read Orlando Furioso, which means Crazy Roland, crazy for love, of course, to find out.

The old Indo-European great-granddaddy of our Word of the Week, fly, certainly got around. He’s the root plewk-, to fly (through the air), son of plew-, to move smoothly and quickly, that is, to flow, and the brother of plewd-, to fly (through the water), that is, to float. So we have a flock of birds and a fleet of ships, just because of the different consonants that were added to the root to tell what it was you were flowing through. Descendants are everywhere, as in Latin pluvius, rain; Greek ploion, boat; Serbian pluto, cork — for corks float! But I think the most unusual relation, a kind of half-cousin fourteen times removed, is English pulmonary, from Latin pulmo, lung — so called because lungs are the floaters; they float on water. That’s why English deer hunters used to call them the lights, and not because they shone!

Word & Song is an online magazine devoted to reclaiming the good, the beautiful, and the true. We publish six essays each week, on words, classic hymn, poems, films, and popular songs. Paid subscribers receive audio-enhanced posts, a weekly podcast (alternately Poetry Aloud or Anthony Esolen Speaks), access to our full archive of over 700 essays and may contribute their comments.

To support this project, please join us as a free or paid subscriber.