Welcome, everybody, to a short lesson in the history of English!

Every so often, somebody like George Bernard Shaw comes along, insisting that we jigger English spelling so that it will record accurately how we pronounce our words. It seems reasonable, right? Yet we’d lose a lot more than we’d gain by it. First, there’s the little matter that we don’t all pronounce the words in the same way — CLERK is “CLARK” in Chichester but “CLURK” in Chicago; WHICH is “HWITCH” in Ireland and in some pockets of the United States, but “WITCH” everywhere else, and let’s not even get to how we say our L’s and R’s and I’s, or Cockney “URF” for EARTH! Second, English words sometimes change their sounds when the form changes, and if we changed the spelling to reflect the sounds, we would lose the immediate sense of kinship: we say ELEVATE, with a clear T, but it’s ELEVATION for the noun, and do we really want to spell it “ELEVAISHUN”? Third, the old spellings give us clues as to a word’s origin from or relations to words in other languages. We see a word like MACHINE, pronounced MASHEEN, but the old spelling allows us to recognize the word in Latin MACHINA or Italian MACCHINA. Anyway, I don’t think that English spelling is all that hard — nowhere near as hard as French or Gaelic spelling.

Which — or HWICH — brings me to our Word of the Week, know. Oh, that darned KN, the bugbear of little kids trying to spell! Well, we spell it that way because that’s how it used to be pronounced. I think that history shows us what single category of people has been most energetic in inventing alphabets or recording a language in written characters for the first time: Christian missionaries. They really did so wherever they went, if the people did not have those already. And so they did for the Germanic peoples in England. They adapted the Roman alphabet to the Germanic sounds, and they did an excellent job of it, too. They recorded combinations of consonants that didn’t exist in Latin — many of which we take for granted, like SL-, SM-, and SN-, and some of which we don’t have anymore, like WR-, WL-, HN-, HL-, HR-, a few others, and CN-, as in the Old English verb CNAWAN, to KNOW. That CN- faded away over many centuries and was simplified to N-, but by then the standard spelling with KN- had long been fixed in place.

By the way, such things didn’t happen only in English. It happened in the big branch of our family that gave birth to Latin. It’s why we have English SLIME, but Latin LIMUS, “mud,” and English SLIPPERY, but Latin LUBRICUS, which means the same thing. They lost the SL-, reduced to L; see, what we find easy to say, speakers of other languages don’t at all! And things don’t always get smoothed out over time. Sometimes they clump up. Think it’s hard to say CN-? Try saying Italian SBRIGATI, meaning “HURRY UP!” — with a ZBR — and Italian has a lot of those. It’s because the prefix DIS- was reduced to S-, so they lost the syllable, and gained some really peculiar clusters of consonants at the beginnings of such words, and they’re common ones, too.

Anyway, the monks were really careful to render what they heard, as precisely as they could, so they’re a great source of reliable information for us historians of language. And when they came on a sound that the Roman alphabet couldn’t represent, they invented new characters, including the quite clever æ, which they called “æsc,” that is, “ash”. Try pronouncing, in succession, ah, a (as in bat), e (as in bet). Notice where your tongue is. Doesn’t it move from low in the middle, to low in front, to a little higher in front? The sound in that way is right between ah and eh. So what better way to spell it, than with a and e crushed together?

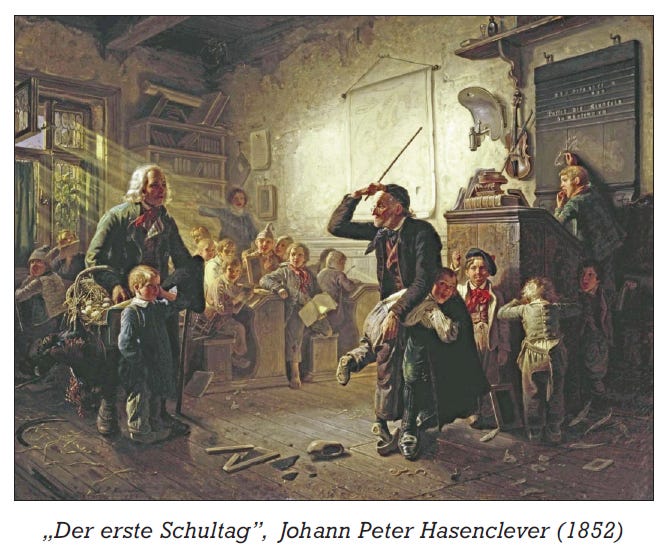

’ll have more to say this week about what the word know means. I’ll say here at the outset that the more you think about what a human being means when he says, “I know,” the more fascinating and mysterious it is. Our dog Molly knows. She knows that the leash means she’s going for a walk. She knows that if I’m eating a cookie I’ll give her a little piece of it. But she’s not aware that she knows it. Our dog Jasper of happy memory did 75 tricks on command, which is more than most politicians can do, but he didn’t think about them, he didn’t weigh them, he didn’t relate them to other things, he didn’t imagine new tricks — well, with Jasper, you could never be sure about that! And we can also consider that how we know something varies with the object. For example, I know that my favorite pitcher of all time, Bob Gibson, had an Earned Run Average of 1.12 in 1968, over more than 300 innings. It is why a picture of that record ought to illustrate the word “microscopic” in the dictionary. But I also say that I know what it is to feel joy — so different from pleasure! How can I explain it? And what do we mean when we say that we know another human being? In some measure, we know the unknowable God himself, by his own revelation. But here we are on the verge of an unfathomable abyss. Because God exists, knowledge has no limit — no bounds in space or matter or time. It can never pass away.

Word & Song by Anthony Esolen is an online magazine devoted to reclaiming the good, the beautiful, and the true. We publish six essays each week, on words, classic hymn, poems, films, and popular songs, as well a weekly podcast, alternately Poetry Aloud or Anthony Esolen Speaks. Subscribe below.

We think of our Word & Song archive as a little treasure trove. Our paid subscribers have on demand access to the entire of Word & Song, many hundreds of entries. We hope that all of our readers will revisit and share our posts with others as we continue our mission of reclaiming — one thing at a time — the good, the beautiful, and the true.