Who better to write a poem about laughter than the apostle of good cheer, G. K. Chesterton?

At the school where I taught for 27 years, most of them very happy, there’s a hallway full of old photographs, and in one of them, pretty grainy, you can see Chesterton, burly and shaggy as ever, after he’d given a speech to the student body. That was on December 11, 1930. The students were outdoors, below, as Chesterton delivered his talk from a very small and tight balcony projecting from the second floor of Harkins Hall, which was originally the college in its entirety. The boys didn’t mind the cold. I’ve been told that Chesterton could hardly fit through the narrow door, and it took a couple of men to help him to get back inside. He’s the sort of man who’d have taken that as a terrific jest. Here’s part of a report on the day, from the student literary magazine:

“The great literary dictator, Gilbert Keith Chesterton, addressed the student body on the morning of December 11th, 1930, and attended a luncheon given by the faculty in his honor… In his own inimitable way, this renowned lecturer, poet, essayist, and critic won his way into our hearts with his smile and a harmonious flow of simple, yet intriguing, diction that suggested rather than conveyed the sparkling epigram, the humorous quirk, the startling paradox that lurk in the mind of a man whose thoughts come in battalions. He wasn’t aware, he told us, that he really had any message to offer us, but he was sure that he wouldn’t try our patience as he had that of the boys at Notre Dame, who had marvelous powers of endurance and a wonderful capacity for pain, as attested by their suffering him to afflict them with no less than thirty-six-lectures. (Parenthetically, he confided to us that his best Parisian accent couldn’t master the American mode of designating the Alma Mater of the Irish from South Bend.) He was pleased to visit Providence College because of the auspices of the Dominicans. Many preaching friars in England were dear friends of his, he averred, particularly Father Vincent McNabb, who is one of the truly great minds of the present time, and, therefore not mentioned by the newspapers…”

Father McNabb, by the way, was another man of laughter, and courage too — I’d love to have heard him debate that other friend of Chesterton’s, the equally bluff but not equally pious George Bernard Shaw. Surely there were giants in those days!

There are a lot of things that Chesterton always enjoyed taking apart with his keen attention and his irrepressible wit. One of them was materialism in all its forms. C. S. Lewis took it on too, but in a different way; there always was a bit of the sober Ulsterman in Lewis, or, maybe to put it more accurately, a bit of that grumbly and saintly Marsh-wiggle of happy memory, Puddleglum. We can sum up materialism as a philosophy with the adverb only. Whenever you hear it, be on your guard. Thought is “only” the skittering of neurons in your head. Really? Isn’t that like saying that the Mona Lisa is “only” an array of pigments on a canvas — only the material substrate? Love is “only” the way your genes make themselves immortal. Really? Remarkably creative, those genes! They could write Romeo and Juliet, Pride and Prejudice, O Pioneers!, Sonnets from the Portuguese; and it was only genes that moved my father to breathe out his last dying words to my mother, “I love you.” Really? Religion came about only because primitive man was trying to explain thunder and lightning and other things around him. Really? Primitive man was as one-dimensional as that? Had no feelings of awe, no sense of beauty, no approach to the mystery of being?

I’ll add here that medieval man was quite aware of what Aristotle called the material cause of a thing, namely the matter that composed it. They simply did not suppose, in a lazy or flippant way, that that was all there was to it. They had Aristotle on their side, too.

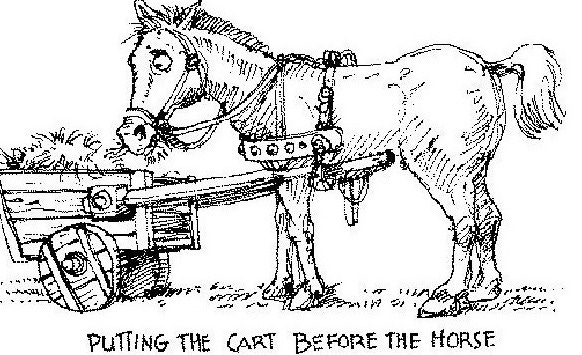

Our Poem of the Week takes on the “only,” by turning the reductive analysis upside down. If the boy taking up his first “fighting” stance — does Chesterton mean that he’s kicking in the womb? — is “only” a tadpole under the scum of a pond, well, we might say, “We’d never suspected the frog had it in him!” It’s Chesterton’s way of looking at the supposed origins as more, far more than the materialist supposes, and laughing merrily to boot. That’s if it’s as the materialist says — but, Chesterton asks, taking a lance to all these “just so” stories, is that really true after all? The poem reaches its climax in the third stanza, because here we’re not talking about the materialist’s reduction, but the historicist’s. The Virgin Mary? Just like Isis, just like Cybele! Really? They aren’t the slightest bit like her, but, Chesterton asks, if you flatter them by the comparison, what on earth do you think you’re doing to him?

That’s Chesterton, not snarling, not angry, but breaking out into merry laughter. We could use somebody like that now!

Say to the lover when the lane Thrills through its leaves to feel her feet, “You only feel what smashed the slime When the first monstrous brutes could meet.” Shall not the lover laugh and say (Whom God gives season to be gay), “Well for those monsters long ago If that be so; but was it so?” Say to the mother when the son First springs and stiffens as for fight, “So under that green roof of scum The tadpole is the frog’s delight, So deep your brutish instincts lie.” She will laugh loud enough and cry, “Then the poor frog is not so poor. O happy frog! But are you sure?” Ye learned, ye that never laugh, But say, “Such love and litany Hailed Isis; and such men as you Danced by the cart of Cybele,” Shall not I say, “Your cart at least Goes far before your horse, poor beast. Like Her! You flatter them maybe. What do you think you do to me?”

Listen to this episode with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Word & Song by Anthony Esolen to listen to this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.