When I was a boy, I walked every day back and forth to school, crossing what everybody called The River, over one of the three bridges in town, each only a few hundred yards away from the other. The River was and still is the Lackawanna River, possibly the shortest river to get mentioned in my encyclopedia. It’s only 55 miles long, though it runs through what used to be the richest anthracite coal fields in the world. There’s no coal mining there anymore, but downriver there’s still a lot of seepage from the old mines, and for the last three or four miles of the river before it flows into the Susquehanna. No fish could live in it in my town, back in those days, but we’ve cleaned it up considerably, and now it’s alive again. The towns have turned an old Delaware & Hudson train bed beside the river into a nice trail for walking and biking, and it really is quite pretty.

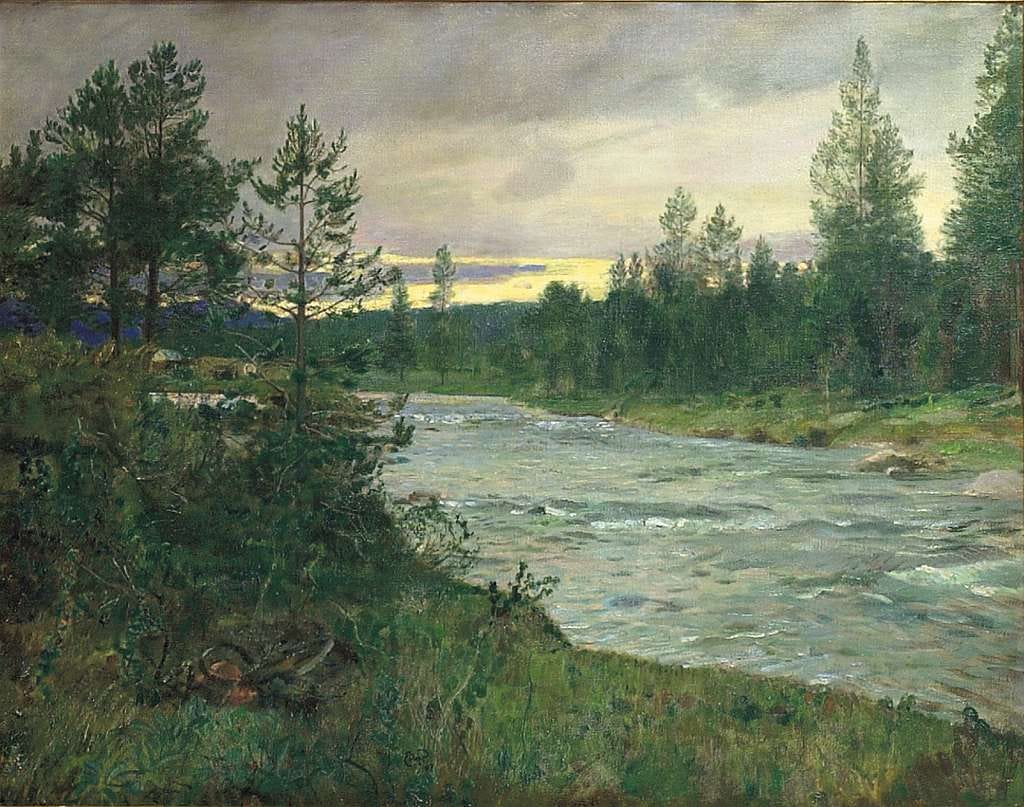

What fascinated me most about The River wasn’t whether there were fish in it, but that it was a river at all — that it flowed. Is it so with all people, I wonder? I’d lean out over the rail of the bridge, just as all the kids did, I suppose, and watch the water in its channel twenty feet below, and often I’d see the sun flashing on it from the southwest, and the wavelets lapping against the bridgework, or the hummock in the middle of the water downstream, forming an “island” that you’d see unless the water was very high, and I’d think — or rather I wouldn’t think, because The River was all my thought.

Is there a boy alive who doesn’t spit into a river or toss a stick into it just to see it flow away? Why did we love it? We couldn’t swim in it. When the rain was coming on or the air sat heavy upon us, you’d catch an odd whiff of sulfur, and you’d say, “There’s the River!” The River was always the same, but never the same. It stayed where it was, but it never stayed for a moment. It was always at rest, and always in act. You’d see nothing new in it, but it was always new, because the water was flowing, and no two splashes of water over a rock are exactly the same.

Since then, I’ve seen a few of the world’s great rivers — the Ohio, the Mississippi, the Missouri, the Saint Lawrence, the Danube, the Rhine; and others, though not so great, famous or peculiar in one way or another; the Arno, flowing beneath the Ponte Vecchio that Dante crossed, or Father Tiber, sluggishly settling town to Rome’s port at Ostia, or the mighty Po, only a fourth of the length of the Rio Grande, but sending more than twenty times as much water into the sea, and making its rolling way through some of the best farmland in the Mediterranean, not to mention cities more than two thousand years old. And I’m fascinated by rivers I’ve never seen — the Yangtze, bounded by steep and breathtakingly beautiful cliffs for two hundred miles through the Three Gorges; the Ganges, the holy river of India, with its millions of pilgrims bathing in its waters every year, to be cleansed and made new, as they believe; and most of all the Jordan swift and clear, where John baptized and Jesus preached the kingdom of God. I imagine that the evangelist John had an affection for rivers, too, as he saw the pure river, the water of life, flowing from the throne of God and the Lamb.

Our Old English word for river was ea, a cousin of Latin aqua, water, and both of them probably cousins with Hindi ab, river, as in the Punj-ab, the Region of the Five Rivers, and with Gaelic abhainn — as in the Avon River, which would then be the “River” River. But that word’s been lost, replaced in the Middle Ages by the Old French rivere, from Latin riparius, having to do with a ripa or a steep riverbank. For the word ripa comes not from anything with water in it, but from a root meaning to cut, to tear off, as you’d suddenly have your way cut off when you approached the banks of the Mississippi from the eastern side at Minneapolis: it’s bounded by quite an imposing bluff. But if you could just mosey on over to the river and dip your toe in it, that edge wouldn’t be called a ripa, in Latin use. In any case, if you arrive somewhere, it means that you’ve come across the sea or along the river and you have set foot upon the ripa, the banks. Dante thus imagines the souls making their way from the Tiber across the ocean to arrive at the banks of the Mountain of Purgatory, which means that they will all be saved. But not those who gather at the banks of the River Acheron! Not a good day for them, and where that river flows, well — you have to read Dante to find out.

Word & Song is an online magazine devoted to reclaiming the good, the beautiful, and the true. We publish six essays each week, on words, classic hymns, poems, films, and popular songs, as well a weekly podcast for paid subscribers, alternately Poetry Aloud or Anthony Esolen Speaks. Paid subscribers also receive audio-enhanced posts and on-demand access to our full archive, and may add their comments to our posts and discussions.

To support this project, please join us as a free or paid subscriber.