“Red sky at night, sailor’s delight,” went the old jingle, and, “Red sky at morning, sailors take warning.” That ancient wisdom can be found in the words of Jesus, when the Pharisees and the Sadducees demand from Jesus a sign from heaven. Putting him to the test, they were, because they didn’t want to heed his words and consider all the people he had healed. So Jesus said that they knew well enough to predict fair weather when the sky was red at evening, and foul weather when the sky was red at morning, but they could not discern the signs of the times. The sailors and shepherds and farmers were right about the red sky. High pressure systems can capture a lot of particles of dust, and it’s those that make for the red sky when the sun is low to the horizon, because the particles obstruct more of the rays of light from the blue end of the spectrum. Call it a little bit of recompense for living in a city with smokestacks. Now, we look to the west for the weather that’s coming our way, because that’s how the earth is turning; so a high in the west at sunset means that a nice day is coming. But a high in the east means that it’s going, and a low is rushing in.

Anyway, our Word of the Week, sky, is a favorite of mine, both for what it names and for what it doesn’t name. What I mean is that in English, we’ve got two words, one for the sky above us, and one for heaven, the realm of God. In most languages, one word does duty for both: German Himmel, Italian cielo, Greek ouranos. So when Dante’s ferryman, in the Inferno, welcomes the souls gathered at the Acheron with this bit of news, “Non isperate mai veder lo cielo,” you could translate it with either heaven or sky — and since, if you’re never going to see the sky, you sure aren’t going to see heaven either, I’ve translated it as, “Give up all hope to look upon the skies!” Talk about cause for claustrophobia!

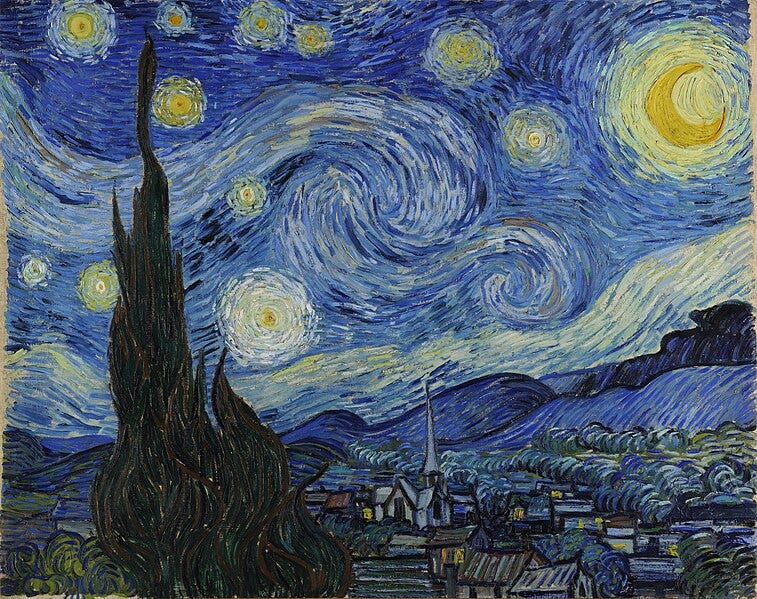

For it is a mystery, that man looks to the sky, with love, with wonder. No other creature does that. I take our puppy Molly out for a short walk at night, and the first thing I do is what I guess everybody does. I look up at the sky. I don’t do so just because of the weather. I want to see the moon, the stars, and whatever planet might be hanging about. I want to see those beautiful and faraway things. I behold them: no other creature on earth beholds, to gaze at a beautiful thing for the sake of it and no purpose beyond the delight. And I’ve done so from the time I was a little child, as we all have done. One night, when I was five years old, I was walking with my mother down our street, and I looked to the north and said, “There’s Cassiopeia.” “There’s — what?” she said, so I showed her the sideways W-constellation, and said, “That’s Cassiopeia.” I’d read it in the encyclopedia. And the other night, when I was up far too late, I looked to the southeast and saw a bright and deep red star in a snake-like constellation, and said, “Antares!” — as if it were an old friend. Imagine, if somebody said to you, “From this day on, you will never see the sky. We’ll feed you and give you a lot of things to divert you, but as for the sky, forget it.” You’d say, “No — I’ll take anything but that!” It’s as if our love for the sky is a sort of bright shadow of our longing for heaven. We can’t be human without it.

You’ll likely be surprised by where our word sky comes from. Most of our sk- words come from the Scandinavians who settled in the northeast of England; that’s because that combination of consonants in Old English had turned into the sound sh- (same in Old High German, too). So we get doublets like skirt (from the north) and shirt (everywhere else), or scatter (from the north) and shatter (everywhere else). The word sky originally referred to the clouds up there: hence the plural skies. Yes, the clouds, since sky comes from a root that means to cover up, to darken: it’s a cousin of Greek skotia, darkness, and English shadow. What long and winding roads a word can take!